Dec 15, 2025

Competitiveness Is the Key to Meaningful Redistricting Reform

David Froomkin

,

Ian Shapiro

Dec 15, 2025

Competitiveness Is the Key to Meaningful Redistricting Reform

David Froomkin

,

Ian Shapiro

Dec 15, 2025

Competitiveness Is the Key to Meaningful Redistricting Reform

David Froomkin

,

Ian Shapiro

Dec 15, 2025

Competitiveness Is the Key to Meaningful Redistricting Reform

David Froomkin

,

Ian Shapiro

Dec 15, 2025

Competitiveness Is the Key to Meaningful Redistricting Reform

David Froomkin

,

Ian Shapiro

Dec 15, 2025

Competitiveness Is the Key to Meaningful Redistricting Reform

David Froomkin

,

Ian Shapiro

Redistricting might seem like a strange place to look for optimism about democratic institutions. We are in the midst of a partisan gerrymandering war—kicked off by Texas in response to pressure from the White House—that is contributing in no small part to the degradation of American democracy. In the immediate future, congressional representation will likely become more distorted than it has been in recent memory. But it is far from clear that a return to the status quo ante would be optimal, and the gerrymandering war has raised the profile of the problem. In a few years there might either be federal legislation adopting a uniform approach to redistricting or at least a state-level backlash. Either is a plausible pathway to widespread adoption of independent redistricting commissions. Indeed, mandating that states adopt independent redistricting commissions was an element of Democrats’ abortive democracy reform agenda in 2021, and it will likely be part of a democracy reform agenda for 2029.

American democracy is in tatters. Many of its institutions have proved brittle. But some are easier to reform than others, and some reforms offer more bang for the buck. The redistricting process deserves particular attention, because it is enormously consequential for the health of democracy and also amenable to reforms without constitutional amendment—including through the passage of federal legislation under Congress’s Elections Clause authority. Reforming redistricting also poses less of a threat to the dominant parties than more far-reaching electoral reforms, such as a transition to proportional representation. Indeed, establishment figures in the dominant parties might themselves have an interest in redistricting reforms that reduce the system’s vulnerability to hijacking by extremists.

Substantial redistricting reforms have occurred at the state level in recent decades— although the emerging gerrymandering war threatens to roll back that progress. In particular, many states have moved toward independent redistricting commissions. Independent commissions have the potential to sideline politicians who might seek to draw maps that frustrate the interests of voters. But simply establishing a commission is not a panacea, because there remains the crucial question of what criteria the commission will use. Indeed, many commissions rely on the same criteria as legislatures traditionally have used, either because they are instructed by law to do so or because they are conscious of the need to draw politically palatable maps. When a commission’s map must be approved by the legislature, for instance, the commission will take lawmakers’ preferences for incumbency protection into account. In drawing maps, legislatures tend to prioritize incumbency protection, resulting in the creation of a large number of safe seats. When commissions follow suit, they undermine the potential benefits of the commission model.

The proliferation of safe seats is bad for democracy. The ultimate consequence is a dysfunctional legislature that fails to act on issues of mainstream concern. There are two main reasons. First, safe seats undermine electoral competition. In a safe seat, electoral challengers outside of the majority party have little chance of winning an election. The absence of competition means that members of the majority party have little incentive to perform well. When incumbents’ reelection does not hinge on delivering policies that are broadly popular, incumbents can instead shirk their responsibilities and focus on symbolic appeals to their core supporters. Competition is also how a democracy identifies which agendas deserve to be pursued. Americans need clear choices between alternative programs in order to judge whether they are being well-served by their representatives. Second, safe seats facilitate extremism. In safe seats, politicians are more responsive to a partisan base than to the views of the statewide (much less nationwide) electorate.

The dominance of safe seats is a result of a particular philosophy about representation. The dominant approach to redistricting aims to give representation to discrete constituencies. As a result, districts tend to represent either predominantly urban or predominantly rural voters. In order to win in these geographically-segregated districts, politicians must take positions far from that of the median voter. Even when redistricting does not prioritize incumbency protection, geographic segregation tends to create culturally and politically homogeneous districts. These kinds of districts reward politicians for making sectarian appeals rather than advancing encompassing policies that benefit voters broadly. Districts constructed to include a more pluralistic cross-section of the population would encourage politicians to appeal more to mainstream opinion and to deliver policies that advance widely shared interests.

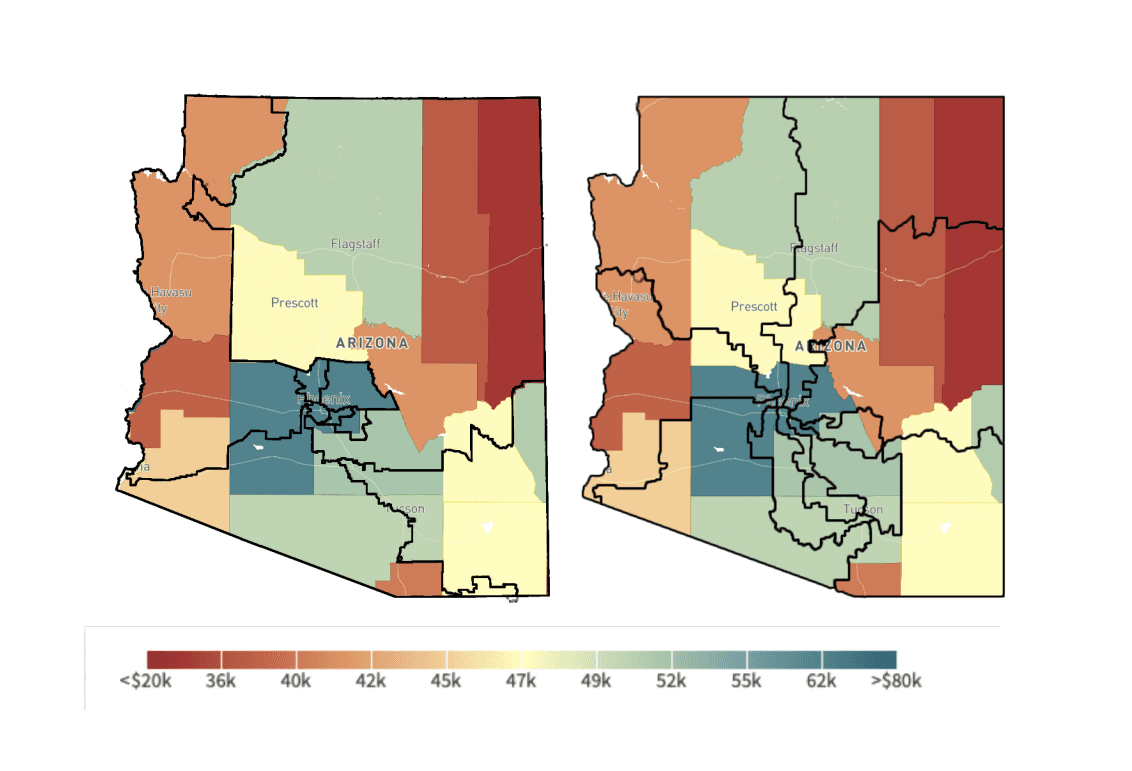

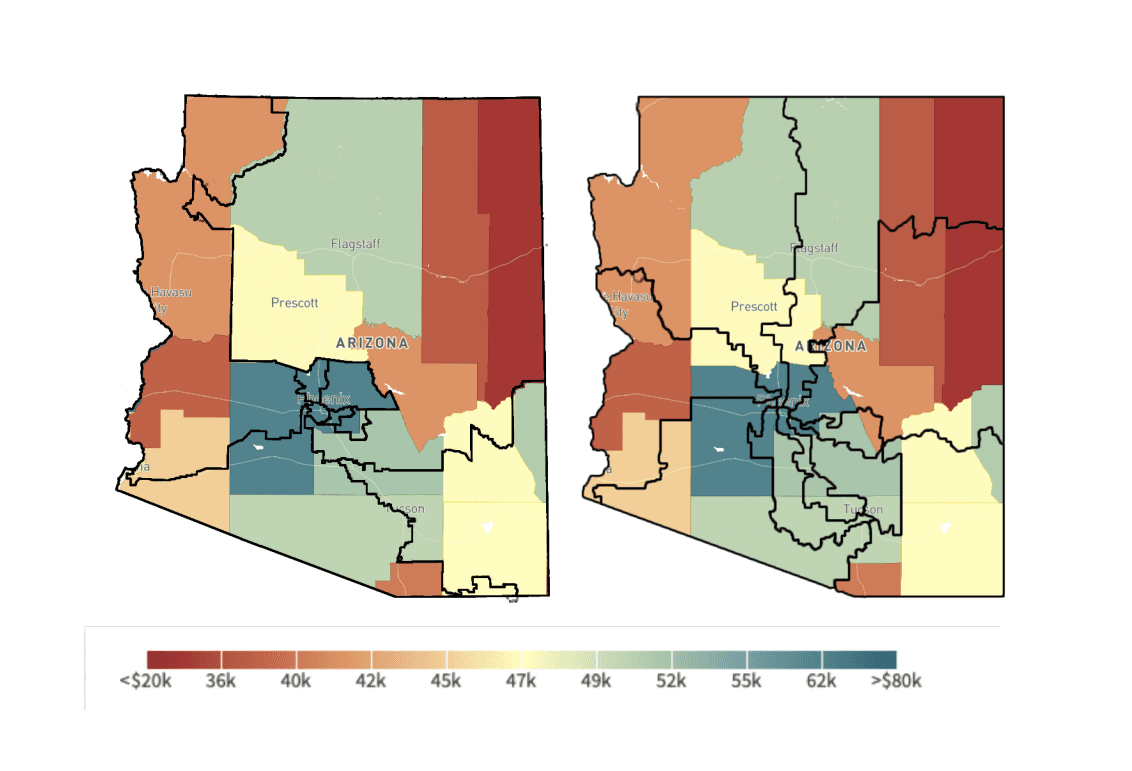

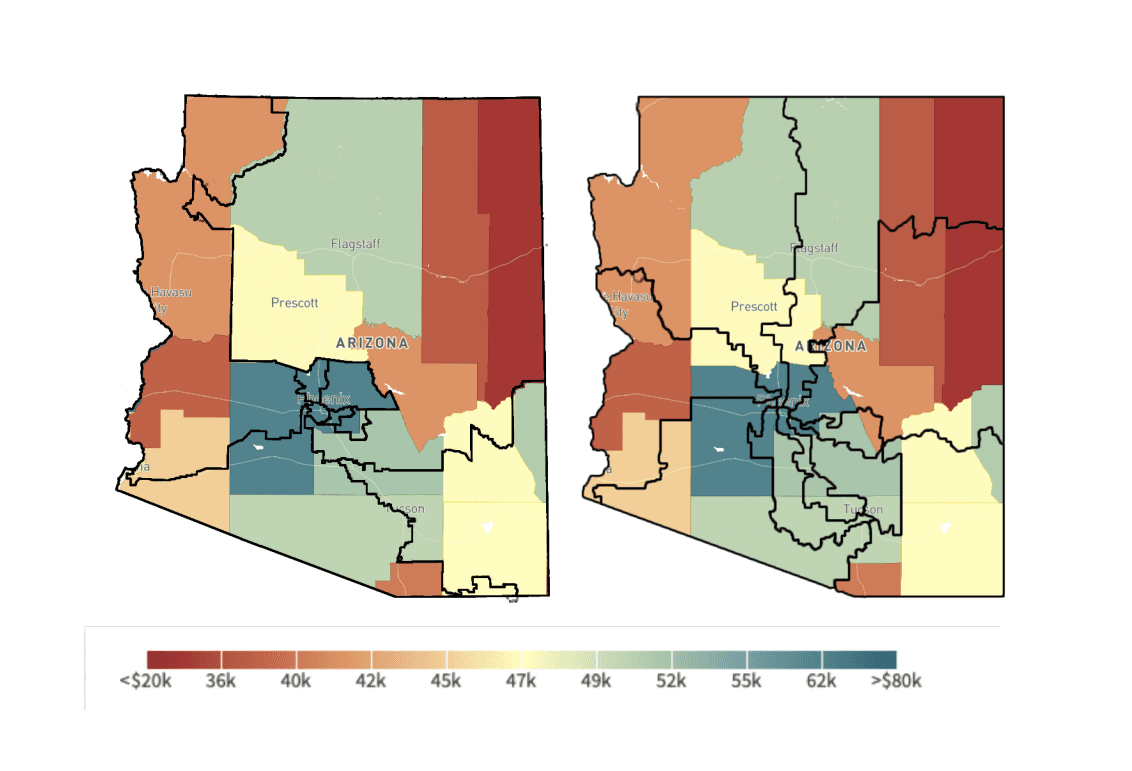

Rather than using criteria that produce geographically and culturally segregated districts, carving up a state into safe Democratic and Republican seats, it would be better for mapmakers to prioritize drawing competitive districts. The following maps illustrate the difference between the prevailing geography-based approach and an alternative competitiveness-based approach.

On the left is Arizona’s current congressional map, which largely segregates urban and rural constituencies. On the right is an alternative map that would maximize plurality within districts. This competitiveness-oriented map follows the principle that each legislative district in the state should contain a microcosm of the diversity of the state. (This particular map is the result of maximizing average income diversity across districts.) Plurality is the key to accountability. Democracy should reward politicians who deliver popular, broad-based policies. Diverse districts force politicians to appeal to the mainstream of state opinion, rather than to an unrepresentative subset. Balkanized districts, by contrast, encourage grandstanding, sectarianism, and extremism.

Redistricting might seem like a strange place to look for optimism about democratic institutions. We are in the midst of a partisan gerrymandering war—kicked off by Texas in response to pressure from the White House—that is contributing in no small part to the degradation of American democracy. In the immediate future, congressional representation will likely become more distorted than it has been in recent memory. But it is far from clear that a return to the status quo ante would be optimal, and the gerrymandering war has raised the profile of the problem. In a few years there might either be federal legislation adopting a uniform approach to redistricting or at least a state-level backlash. Either is a plausible pathway to widespread adoption of independent redistricting commissions. Indeed, mandating that states adopt independent redistricting commissions was an element of Democrats’ abortive democracy reform agenda in 2021, and it will likely be part of a democracy reform agenda for 2029.

American democracy is in tatters. Many of its institutions have proved brittle. But some are easier to reform than others, and some reforms offer more bang for the buck. The redistricting process deserves particular attention, because it is enormously consequential for the health of democracy and also amenable to reforms without constitutional amendment—including through the passage of federal legislation under Congress’s Elections Clause authority. Reforming redistricting also poses less of a threat to the dominant parties than more far-reaching electoral reforms, such as a transition to proportional representation. Indeed, establishment figures in the dominant parties might themselves have an interest in redistricting reforms that reduce the system’s vulnerability to hijacking by extremists.

Substantial redistricting reforms have occurred at the state level in recent decades— although the emerging gerrymandering war threatens to roll back that progress. In particular, many states have moved toward independent redistricting commissions. Independent commissions have the potential to sideline politicians who might seek to draw maps that frustrate the interests of voters. But simply establishing a commission is not a panacea, because there remains the crucial question of what criteria the commission will use. Indeed, many commissions rely on the same criteria as legislatures traditionally have used, either because they are instructed by law to do so or because they are conscious of the need to draw politically palatable maps. When a commission’s map must be approved by the legislature, for instance, the commission will take lawmakers’ preferences for incumbency protection into account. In drawing maps, legislatures tend to prioritize incumbency protection, resulting in the creation of a large number of safe seats. When commissions follow suit, they undermine the potential benefits of the commission model.

The proliferation of safe seats is bad for democracy. The ultimate consequence is a dysfunctional legislature that fails to act on issues of mainstream concern. There are two main reasons. First, safe seats undermine electoral competition. In a safe seat, electoral challengers outside of the majority party have little chance of winning an election. The absence of competition means that members of the majority party have little incentive to perform well. When incumbents’ reelection does not hinge on delivering policies that are broadly popular, incumbents can instead shirk their responsibilities and focus on symbolic appeals to their core supporters. Competition is also how a democracy identifies which agendas deserve to be pursued. Americans need clear choices between alternative programs in order to judge whether they are being well-served by their representatives. Second, safe seats facilitate extremism. In safe seats, politicians are more responsive to a partisan base than to the views of the statewide (much less nationwide) electorate.

The dominance of safe seats is a result of a particular philosophy about representation. The dominant approach to redistricting aims to give representation to discrete constituencies. As a result, districts tend to represent either predominantly urban or predominantly rural voters. In order to win in these geographically-segregated districts, politicians must take positions far from that of the median voter. Even when redistricting does not prioritize incumbency protection, geographic segregation tends to create culturally and politically homogeneous districts. These kinds of districts reward politicians for making sectarian appeals rather than advancing encompassing policies that benefit voters broadly. Districts constructed to include a more pluralistic cross-section of the population would encourage politicians to appeal more to mainstream opinion and to deliver policies that advance widely shared interests.

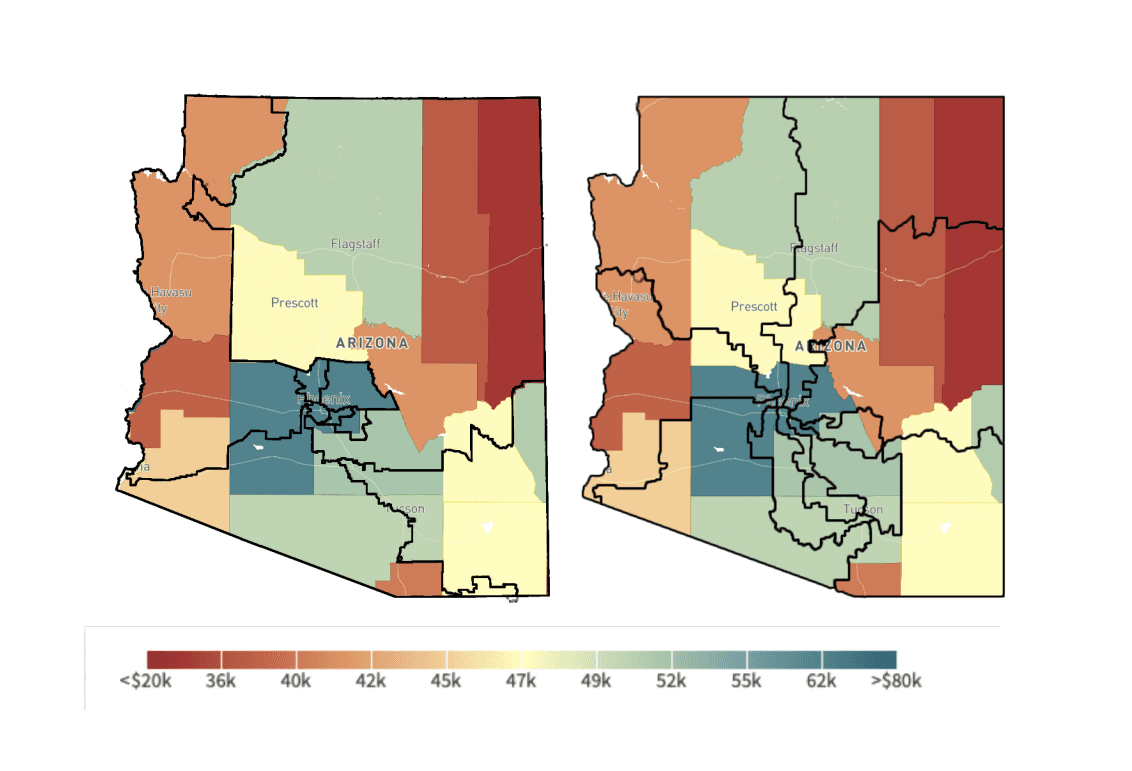

Rather than using criteria that produce geographically and culturally segregated districts, carving up a state into safe Democratic and Republican seats, it would be better for mapmakers to prioritize drawing competitive districts. The following maps illustrate the difference between the prevailing geography-based approach and an alternative competitiveness-based approach.

On the left is Arizona’s current congressional map, which largely segregates urban and rural constituencies. On the right is an alternative map that would maximize plurality within districts. This competitiveness-oriented map follows the principle that each legislative district in the state should contain a microcosm of the diversity of the state. (This particular map is the result of maximizing average income diversity across districts.) Plurality is the key to accountability. Democracy should reward politicians who deliver popular, broad-based policies. Diverse districts force politicians to appeal to the mainstream of state opinion, rather than to an unrepresentative subset. Balkanized districts, by contrast, encourage grandstanding, sectarianism, and extremism.

Redistricting might seem like a strange place to look for optimism about democratic institutions. We are in the midst of a partisan gerrymandering war—kicked off by Texas in response to pressure from the White House—that is contributing in no small part to the degradation of American democracy. In the immediate future, congressional representation will likely become more distorted than it has been in recent memory. But it is far from clear that a return to the status quo ante would be optimal, and the gerrymandering war has raised the profile of the problem. In a few years there might either be federal legislation adopting a uniform approach to redistricting or at least a state-level backlash. Either is a plausible pathway to widespread adoption of independent redistricting commissions. Indeed, mandating that states adopt independent redistricting commissions was an element of Democrats’ abortive democracy reform agenda in 2021, and it will likely be part of a democracy reform agenda for 2029.

American democracy is in tatters. Many of its institutions have proved brittle. But some are easier to reform than others, and some reforms offer more bang for the buck. The redistricting process deserves particular attention, because it is enormously consequential for the health of democracy and also amenable to reforms without constitutional amendment—including through the passage of federal legislation under Congress’s Elections Clause authority. Reforming redistricting also poses less of a threat to the dominant parties than more far-reaching electoral reforms, such as a transition to proportional representation. Indeed, establishment figures in the dominant parties might themselves have an interest in redistricting reforms that reduce the system’s vulnerability to hijacking by extremists.

Substantial redistricting reforms have occurred at the state level in recent decades— although the emerging gerrymandering war threatens to roll back that progress. In particular, many states have moved toward independent redistricting commissions. Independent commissions have the potential to sideline politicians who might seek to draw maps that frustrate the interests of voters. But simply establishing a commission is not a panacea, because there remains the crucial question of what criteria the commission will use. Indeed, many commissions rely on the same criteria as legislatures traditionally have used, either because they are instructed by law to do so or because they are conscious of the need to draw politically palatable maps. When a commission’s map must be approved by the legislature, for instance, the commission will take lawmakers’ preferences for incumbency protection into account. In drawing maps, legislatures tend to prioritize incumbency protection, resulting in the creation of a large number of safe seats. When commissions follow suit, they undermine the potential benefits of the commission model.

The proliferation of safe seats is bad for democracy. The ultimate consequence is a dysfunctional legislature that fails to act on issues of mainstream concern. There are two main reasons. First, safe seats undermine electoral competition. In a safe seat, electoral challengers outside of the majority party have little chance of winning an election. The absence of competition means that members of the majority party have little incentive to perform well. When incumbents’ reelection does not hinge on delivering policies that are broadly popular, incumbents can instead shirk their responsibilities and focus on symbolic appeals to their core supporters. Competition is also how a democracy identifies which agendas deserve to be pursued. Americans need clear choices between alternative programs in order to judge whether they are being well-served by their representatives. Second, safe seats facilitate extremism. In safe seats, politicians are more responsive to a partisan base than to the views of the statewide (much less nationwide) electorate.

The dominance of safe seats is a result of a particular philosophy about representation. The dominant approach to redistricting aims to give representation to discrete constituencies. As a result, districts tend to represent either predominantly urban or predominantly rural voters. In order to win in these geographically-segregated districts, politicians must take positions far from that of the median voter. Even when redistricting does not prioritize incumbency protection, geographic segregation tends to create culturally and politically homogeneous districts. These kinds of districts reward politicians for making sectarian appeals rather than advancing encompassing policies that benefit voters broadly. Districts constructed to include a more pluralistic cross-section of the population would encourage politicians to appeal more to mainstream opinion and to deliver policies that advance widely shared interests.

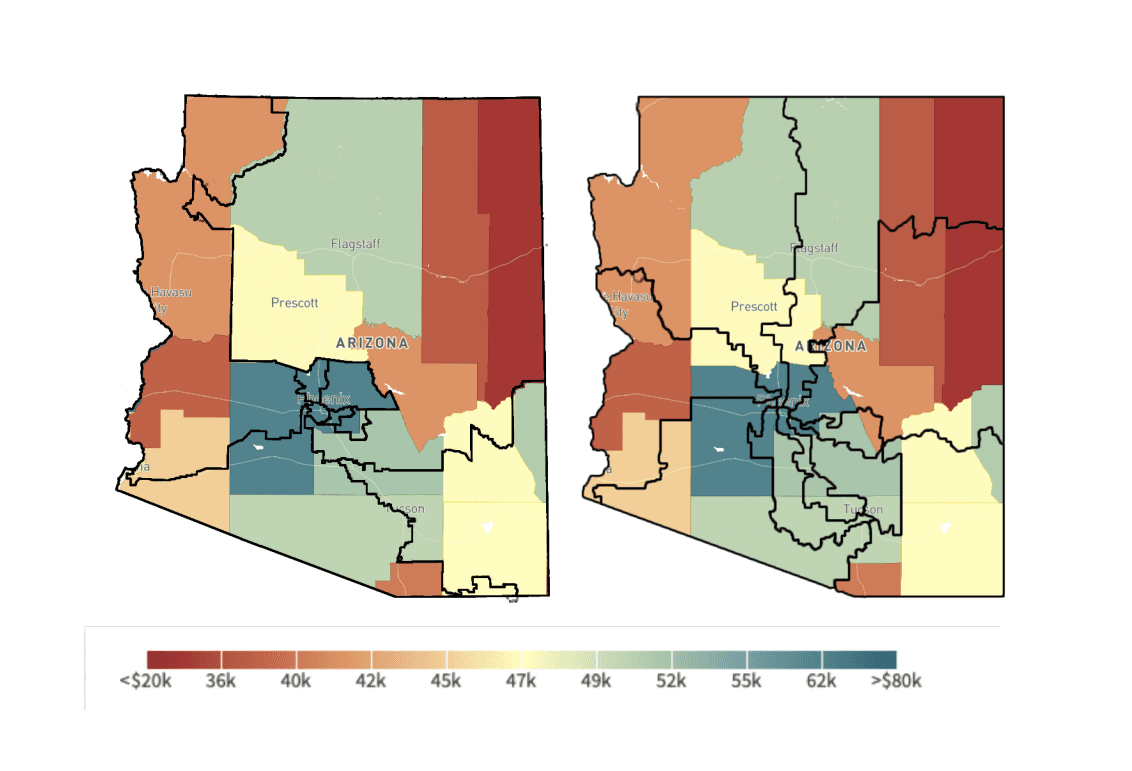

Rather than using criteria that produce geographically and culturally segregated districts, carving up a state into safe Democratic and Republican seats, it would be better for mapmakers to prioritize drawing competitive districts. The following maps illustrate the difference between the prevailing geography-based approach and an alternative competitiveness-based approach.

On the left is Arizona’s current congressional map, which largely segregates urban and rural constituencies. On the right is an alternative map that would maximize plurality within districts. This competitiveness-oriented map follows the principle that each legislative district in the state should contain a microcosm of the diversity of the state. (This particular map is the result of maximizing average income diversity across districts.) Plurality is the key to accountability. Democracy should reward politicians who deliver popular, broad-based policies. Diverse districts force politicians to appeal to the mainstream of state opinion, rather than to an unrepresentative subset. Balkanized districts, by contrast, encourage grandstanding, sectarianism, and extremism.

Redistricting might seem like a strange place to look for optimism about democratic institutions. We are in the midst of a partisan gerrymandering war—kicked off by Texas in response to pressure from the White House—that is contributing in no small part to the degradation of American democracy. In the immediate future, congressional representation will likely become more distorted than it has been in recent memory. But it is far from clear that a return to the status quo ante would be optimal, and the gerrymandering war has raised the profile of the problem. In a few years there might either be federal legislation adopting a uniform approach to redistricting or at least a state-level backlash. Either is a plausible pathway to widespread adoption of independent redistricting commissions. Indeed, mandating that states adopt independent redistricting commissions was an element of Democrats’ abortive democracy reform agenda in 2021, and it will likely be part of a democracy reform agenda for 2029.

American democracy is in tatters. Many of its institutions have proved brittle. But some are easier to reform than others, and some reforms offer more bang for the buck. The redistricting process deserves particular attention, because it is enormously consequential for the health of democracy and also amenable to reforms without constitutional amendment—including through the passage of federal legislation under Congress’s Elections Clause authority. Reforming redistricting also poses less of a threat to the dominant parties than more far-reaching electoral reforms, such as a transition to proportional representation. Indeed, establishment figures in the dominant parties might themselves have an interest in redistricting reforms that reduce the system’s vulnerability to hijacking by extremists.

Substantial redistricting reforms have occurred at the state level in recent decades— although the emerging gerrymandering war threatens to roll back that progress. In particular, many states have moved toward independent redistricting commissions. Independent commissions have the potential to sideline politicians who might seek to draw maps that frustrate the interests of voters. But simply establishing a commission is not a panacea, because there remains the crucial question of what criteria the commission will use. Indeed, many commissions rely on the same criteria as legislatures traditionally have used, either because they are instructed by law to do so or because they are conscious of the need to draw politically palatable maps. When a commission’s map must be approved by the legislature, for instance, the commission will take lawmakers’ preferences for incumbency protection into account. In drawing maps, legislatures tend to prioritize incumbency protection, resulting in the creation of a large number of safe seats. When commissions follow suit, they undermine the potential benefits of the commission model.

The proliferation of safe seats is bad for democracy. The ultimate consequence is a dysfunctional legislature that fails to act on issues of mainstream concern. There are two main reasons. First, safe seats undermine electoral competition. In a safe seat, electoral challengers outside of the majority party have little chance of winning an election. The absence of competition means that members of the majority party have little incentive to perform well. When incumbents’ reelection does not hinge on delivering policies that are broadly popular, incumbents can instead shirk their responsibilities and focus on symbolic appeals to their core supporters. Competition is also how a democracy identifies which agendas deserve to be pursued. Americans need clear choices between alternative programs in order to judge whether they are being well-served by their representatives. Second, safe seats facilitate extremism. In safe seats, politicians are more responsive to a partisan base than to the views of the statewide (much less nationwide) electorate.

The dominance of safe seats is a result of a particular philosophy about representation. The dominant approach to redistricting aims to give representation to discrete constituencies. As a result, districts tend to represent either predominantly urban or predominantly rural voters. In order to win in these geographically-segregated districts, politicians must take positions far from that of the median voter. Even when redistricting does not prioritize incumbency protection, geographic segregation tends to create culturally and politically homogeneous districts. These kinds of districts reward politicians for making sectarian appeals rather than advancing encompassing policies that benefit voters broadly. Districts constructed to include a more pluralistic cross-section of the population would encourage politicians to appeal more to mainstream opinion and to deliver policies that advance widely shared interests.

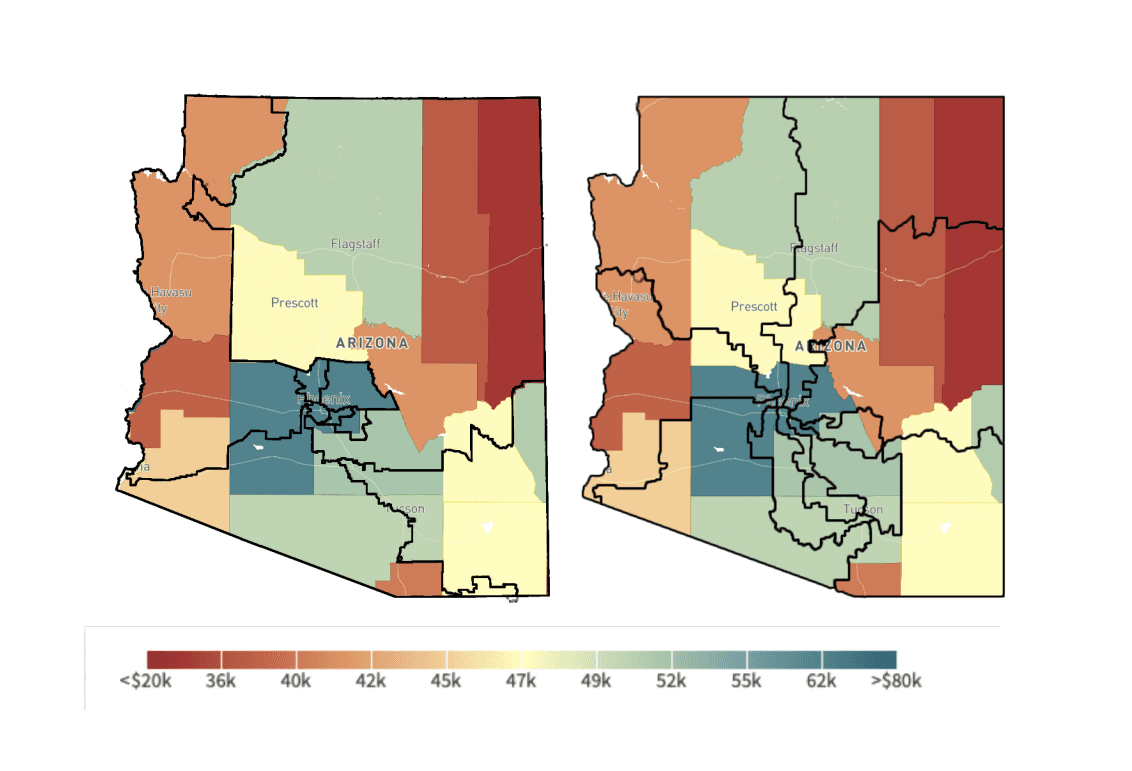

Rather than using criteria that produce geographically and culturally segregated districts, carving up a state into safe Democratic and Republican seats, it would be better for mapmakers to prioritize drawing competitive districts. The following maps illustrate the difference between the prevailing geography-based approach and an alternative competitiveness-based approach.

On the left is Arizona’s current congressional map, which largely segregates urban and rural constituencies. On the right is an alternative map that would maximize plurality within districts. This competitiveness-oriented map follows the principle that each legislative district in the state should contain a microcosm of the diversity of the state. (This particular map is the result of maximizing average income diversity across districts.) Plurality is the key to accountability. Democracy should reward politicians who deliver popular, broad-based policies. Diverse districts force politicians to appeal to the mainstream of state opinion, rather than to an unrepresentative subset. Balkanized districts, by contrast, encourage grandstanding, sectarianism, and extremism.

Redistricting might seem like a strange place to look for optimism about democratic institutions. We are in the midst of a partisan gerrymandering war—kicked off by Texas in response to pressure from the White House—that is contributing in no small part to the degradation of American democracy. In the immediate future, congressional representation will likely become more distorted than it has been in recent memory. But it is far from clear that a return to the status quo ante would be optimal, and the gerrymandering war has raised the profile of the problem. In a few years there might either be federal legislation adopting a uniform approach to redistricting or at least a state-level backlash. Either is a plausible pathway to widespread adoption of independent redistricting commissions. Indeed, mandating that states adopt independent redistricting commissions was an element of Democrats’ abortive democracy reform agenda in 2021, and it will likely be part of a democracy reform agenda for 2029.

American democracy is in tatters. Many of its institutions have proved brittle. But some are easier to reform than others, and some reforms offer more bang for the buck. The redistricting process deserves particular attention, because it is enormously consequential for the health of democracy and also amenable to reforms without constitutional amendment—including through the passage of federal legislation under Congress’s Elections Clause authority. Reforming redistricting also poses less of a threat to the dominant parties than more far-reaching electoral reforms, such as a transition to proportional representation. Indeed, establishment figures in the dominant parties might themselves have an interest in redistricting reforms that reduce the system’s vulnerability to hijacking by extremists.

Substantial redistricting reforms have occurred at the state level in recent decades— although the emerging gerrymandering war threatens to roll back that progress. In particular, many states have moved toward independent redistricting commissions. Independent commissions have the potential to sideline politicians who might seek to draw maps that frustrate the interests of voters. But simply establishing a commission is not a panacea, because there remains the crucial question of what criteria the commission will use. Indeed, many commissions rely on the same criteria as legislatures traditionally have used, either because they are instructed by law to do so or because they are conscious of the need to draw politically palatable maps. When a commission’s map must be approved by the legislature, for instance, the commission will take lawmakers’ preferences for incumbency protection into account. In drawing maps, legislatures tend to prioritize incumbency protection, resulting in the creation of a large number of safe seats. When commissions follow suit, they undermine the potential benefits of the commission model.

The proliferation of safe seats is bad for democracy. The ultimate consequence is a dysfunctional legislature that fails to act on issues of mainstream concern. There are two main reasons. First, safe seats undermine electoral competition. In a safe seat, electoral challengers outside of the majority party have little chance of winning an election. The absence of competition means that members of the majority party have little incentive to perform well. When incumbents’ reelection does not hinge on delivering policies that are broadly popular, incumbents can instead shirk their responsibilities and focus on symbolic appeals to their core supporters. Competition is also how a democracy identifies which agendas deserve to be pursued. Americans need clear choices between alternative programs in order to judge whether they are being well-served by their representatives. Second, safe seats facilitate extremism. In safe seats, politicians are more responsive to a partisan base than to the views of the statewide (much less nationwide) electorate.

The dominance of safe seats is a result of a particular philosophy about representation. The dominant approach to redistricting aims to give representation to discrete constituencies. As a result, districts tend to represent either predominantly urban or predominantly rural voters. In order to win in these geographically-segregated districts, politicians must take positions far from that of the median voter. Even when redistricting does not prioritize incumbency protection, geographic segregation tends to create culturally and politically homogeneous districts. These kinds of districts reward politicians for making sectarian appeals rather than advancing encompassing policies that benefit voters broadly. Districts constructed to include a more pluralistic cross-section of the population would encourage politicians to appeal more to mainstream opinion and to deliver policies that advance widely shared interests.

Rather than using criteria that produce geographically and culturally segregated districts, carving up a state into safe Democratic and Republican seats, it would be better for mapmakers to prioritize drawing competitive districts. The following maps illustrate the difference between the prevailing geography-based approach and an alternative competitiveness-based approach.

On the left is Arizona’s current congressional map, which largely segregates urban and rural constituencies. On the right is an alternative map that would maximize plurality within districts. This competitiveness-oriented map follows the principle that each legislative district in the state should contain a microcosm of the diversity of the state. (This particular map is the result of maximizing average income diversity across districts.) Plurality is the key to accountability. Democracy should reward politicians who deliver popular, broad-based policies. Diverse districts force politicians to appeal to the mainstream of state opinion, rather than to an unrepresentative subset. Balkanized districts, by contrast, encourage grandstanding, sectarianism, and extremism.

Redistricting might seem like a strange place to look for optimism about democratic institutions. We are in the midst of a partisan gerrymandering war—kicked off by Texas in response to pressure from the White House—that is contributing in no small part to the degradation of American democracy. In the immediate future, congressional representation will likely become more distorted than it has been in recent memory. But it is far from clear that a return to the status quo ante would be optimal, and the gerrymandering war has raised the profile of the problem. In a few years there might either be federal legislation adopting a uniform approach to redistricting or at least a state-level backlash. Either is a plausible pathway to widespread adoption of independent redistricting commissions. Indeed, mandating that states adopt independent redistricting commissions was an element of Democrats’ abortive democracy reform agenda in 2021, and it will likely be part of a democracy reform agenda for 2029.

American democracy is in tatters. Many of its institutions have proved brittle. But some are easier to reform than others, and some reforms offer more bang for the buck. The redistricting process deserves particular attention, because it is enormously consequential for the health of democracy and also amenable to reforms without constitutional amendment—including through the passage of federal legislation under Congress’s Elections Clause authority. Reforming redistricting also poses less of a threat to the dominant parties than more far-reaching electoral reforms, such as a transition to proportional representation. Indeed, establishment figures in the dominant parties might themselves have an interest in redistricting reforms that reduce the system’s vulnerability to hijacking by extremists.

Substantial redistricting reforms have occurred at the state level in recent decades— although the emerging gerrymandering war threatens to roll back that progress. In particular, many states have moved toward independent redistricting commissions. Independent commissions have the potential to sideline politicians who might seek to draw maps that frustrate the interests of voters. But simply establishing a commission is not a panacea, because there remains the crucial question of what criteria the commission will use. Indeed, many commissions rely on the same criteria as legislatures traditionally have used, either because they are instructed by law to do so or because they are conscious of the need to draw politically palatable maps. When a commission’s map must be approved by the legislature, for instance, the commission will take lawmakers’ preferences for incumbency protection into account. In drawing maps, legislatures tend to prioritize incumbency protection, resulting in the creation of a large number of safe seats. When commissions follow suit, they undermine the potential benefits of the commission model.

The proliferation of safe seats is bad for democracy. The ultimate consequence is a dysfunctional legislature that fails to act on issues of mainstream concern. There are two main reasons. First, safe seats undermine electoral competition. In a safe seat, electoral challengers outside of the majority party have little chance of winning an election. The absence of competition means that members of the majority party have little incentive to perform well. When incumbents’ reelection does not hinge on delivering policies that are broadly popular, incumbents can instead shirk their responsibilities and focus on symbolic appeals to their core supporters. Competition is also how a democracy identifies which agendas deserve to be pursued. Americans need clear choices between alternative programs in order to judge whether they are being well-served by their representatives. Second, safe seats facilitate extremism. In safe seats, politicians are more responsive to a partisan base than to the views of the statewide (much less nationwide) electorate.

The dominance of safe seats is a result of a particular philosophy about representation. The dominant approach to redistricting aims to give representation to discrete constituencies. As a result, districts tend to represent either predominantly urban or predominantly rural voters. In order to win in these geographically-segregated districts, politicians must take positions far from that of the median voter. Even when redistricting does not prioritize incumbency protection, geographic segregation tends to create culturally and politically homogeneous districts. These kinds of districts reward politicians for making sectarian appeals rather than advancing encompassing policies that benefit voters broadly. Districts constructed to include a more pluralistic cross-section of the population would encourage politicians to appeal more to mainstream opinion and to deliver policies that advance widely shared interests.

Rather than using criteria that produce geographically and culturally segregated districts, carving up a state into safe Democratic and Republican seats, it would be better for mapmakers to prioritize drawing competitive districts. The following maps illustrate the difference between the prevailing geography-based approach and an alternative competitiveness-based approach.

On the left is Arizona’s current congressional map, which largely segregates urban and rural constituencies. On the right is an alternative map that would maximize plurality within districts. This competitiveness-oriented map follows the principle that each legislative district in the state should contain a microcosm of the diversity of the state. (This particular map is the result of maximizing average income diversity across districts.) Plurality is the key to accountability. Democracy should reward politicians who deliver popular, broad-based policies. Diverse districts force politicians to appeal to the mainstream of state opinion, rather than to an unrepresentative subset. Balkanized districts, by contrast, encourage grandstanding, sectarianism, and extremism.

About the Author

David Froomkin

David Froomkin is an assistant professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center and an affiliated faculty member in the Department of Political Science, with primary scholarly interests in administrative law, election law, and democratic and constitutional theory. His research focuses on the structure of government and of the democratic process, drawing on political science and political economy as well as analysis of the text and structure of the Constitution. David received a J.D. from Yale Law School in 2022, and a Ph.D. in Political Science (with distinction) from Yale University in 2024. His dissertation received the Leonard D. White Award from the American Political Science Association for the best dissertation in the field of public administration. His scholarship has been accepted for publication in journals including the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, the Yale Journal on Regulation, and Political Studies. In addition to other ongoing projects, he is currently completing

About the Author

David Froomkin

David Froomkin is an assistant professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center and an affiliated faculty member in the Department of Political Science, with primary scholarly interests in administrative law, election law, and democratic and constitutional theory. His research focuses on the structure of government and of the democratic process, drawing on political science and political economy as well as analysis of the text and structure of the Constitution. David received a J.D. from Yale Law School in 2022, and a Ph.D. in Political Science (with distinction) from Yale University in 2024. His dissertation received the Leonard D. White Award from the American Political Science Association for the best dissertation in the field of public administration. His scholarship has been accepted for publication in journals including the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, the Yale Journal on Regulation, and Political Studies. In addition to other ongoing projects, he is currently completing

About the Author

David Froomkin

David Froomkin is an assistant professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center and an affiliated faculty member in the Department of Political Science, with primary scholarly interests in administrative law, election law, and democratic and constitutional theory. His research focuses on the structure of government and of the democratic process, drawing on political science and political economy as well as analysis of the text and structure of the Constitution. David received a J.D. from Yale Law School in 2022, and a Ph.D. in Political Science (with distinction) from Yale University in 2024. His dissertation received the Leonard D. White Award from the American Political Science Association for the best dissertation in the field of public administration. His scholarship has been accepted for publication in journals including the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, the Yale Journal on Regulation, and Political Studies. In addition to other ongoing projects, he is currently completing

About the Author

David Froomkin

David Froomkin is an assistant professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center and an affiliated faculty member in the Department of Political Science, with primary scholarly interests in administrative law, election law, and democratic and constitutional theory. His research focuses on the structure of government and of the democratic process, drawing on political science and political economy as well as analysis of the text and structure of the Constitution. David received a J.D. from Yale Law School in 2022, and a Ph.D. in Political Science (with distinction) from Yale University in 2024. His dissertation received the Leonard D. White Award from the American Political Science Association for the best dissertation in the field of public administration. His scholarship has been accepted for publication in journals including the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, the Yale Journal on Regulation, and Political Studies. In addition to other ongoing projects, he is currently completing

About the Author

David Froomkin

David Froomkin is an assistant professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center and an affiliated faculty member in the Department of Political Science, with primary scholarly interests in administrative law, election law, and democratic and constitutional theory. His research focuses on the structure of government and of the democratic process, drawing on political science and political economy as well as analysis of the text and structure of the Constitution. David received a J.D. from Yale Law School in 2022, and a Ph.D. in Political Science (with distinction) from Yale University in 2024. His dissertation received the Leonard D. White Award from the American Political Science Association for the best dissertation in the field of public administration. His scholarship has been accepted for publication in journals including the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, the Yale Journal on Regulation, and Political Studies. In addition to other ongoing projects, he is currently completing

About the Author

David Froomkin

David Froomkin is an assistant professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center and an affiliated faculty member in the Department of Political Science, with primary scholarly interests in administrative law, election law, and democratic and constitutional theory. His research focuses on the structure of government and of the democratic process, drawing on political science and political economy as well as analysis of the text and structure of the Constitution. David received a J.D. from Yale Law School in 2022, and a Ph.D. in Political Science (with distinction) from Yale University in 2024. His dissertation received the Leonard D. White Award from the American Political Science Association for the best dissertation in the field of public administration. His scholarship has been accepted for publication in journals including the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, the Yale Journal on Regulation, and Political Studies. In addition to other ongoing projects, he is currently completing

About the Author

Ian Shapiro

Ian Shapiro is the Sterling Professor of Political Science and Global Affairs at Yale University. He has written widely and influentially on democracy, justice, and the methods of social inquiry. His most recent books are "Politics Against Domination" (Harvard University Press, 2016); "Responsible Parties: Saving Democracy from Itself" (Yale University Press, 2018) with Frances Rosenbluth; "The Wolf at the Door: The Menace of Economic Insecurity and how to Fight It" (Harvard University Press, 2020) with Michael Graetz; and "Uncommon Sense" (Yale University Press, 2024). His new book, "After the Fall: From the End of History to the Crisis of Democracy, How Politicians Broke our World" will be published by Basic Books in May 2026.

About the Author

Ian Shapiro

Ian Shapiro is the Sterling Professor of Political Science and Global Affairs at Yale University. He has written widely and influentially on democracy, justice, and the methods of social inquiry. His most recent books are "Politics Against Domination" (Harvard University Press, 2016); "Responsible Parties: Saving Democracy from Itself" (Yale University Press, 2018) with Frances Rosenbluth; "The Wolf at the Door: The Menace of Economic Insecurity and how to Fight It" (Harvard University Press, 2020) with Michael Graetz; and "Uncommon Sense" (Yale University Press, 2024). His new book, "After the Fall: From the End of History to the Crisis of Democracy, How Politicians Broke our World" will be published by Basic Books in May 2026.

About the Author

Ian Shapiro

Ian Shapiro is the Sterling Professor of Political Science and Global Affairs at Yale University. He has written widely and influentially on democracy, justice, and the methods of social inquiry. His most recent books are "Politics Against Domination" (Harvard University Press, 2016); "Responsible Parties: Saving Democracy from Itself" (Yale University Press, 2018) with Frances Rosenbluth; "The Wolf at the Door: The Menace of Economic Insecurity and how to Fight It" (Harvard University Press, 2020) with Michael Graetz; and "Uncommon Sense" (Yale University Press, 2024). His new book, "After the Fall: From the End of History to the Crisis of Democracy, How Politicians Broke our World" will be published by Basic Books in May 2026.

About the Author

Ian Shapiro

Ian Shapiro is the Sterling Professor of Political Science and Global Affairs at Yale University. He has written widely and influentially on democracy, justice, and the methods of social inquiry. His most recent books are "Politics Against Domination" (Harvard University Press, 2016); "Responsible Parties: Saving Democracy from Itself" (Yale University Press, 2018) with Frances Rosenbluth; "The Wolf at the Door: The Menace of Economic Insecurity and how to Fight It" (Harvard University Press, 2020) with Michael Graetz; and "Uncommon Sense" (Yale University Press, 2024). His new book, "After the Fall: From the End of History to the Crisis of Democracy, How Politicians Broke our World" will be published by Basic Books in May 2026.

About the Author

Ian Shapiro

Ian Shapiro is the Sterling Professor of Political Science and Global Affairs at Yale University. He has written widely and influentially on democracy, justice, and the methods of social inquiry. His most recent books are "Politics Against Domination" (Harvard University Press, 2016); "Responsible Parties: Saving Democracy from Itself" (Yale University Press, 2018) with Frances Rosenbluth; "The Wolf at the Door: The Menace of Economic Insecurity and how to Fight It" (Harvard University Press, 2020) with Michael Graetz; and "Uncommon Sense" (Yale University Press, 2024). His new book, "After the Fall: From the End of History to the Crisis of Democracy, How Politicians Broke our World" will be published by Basic Books in May 2026.

More viewpoints in

Elections & Political Parties

Jan 30, 2026

Why Districts?

Paul Rosenzweig

Elections & Political Parties

Jan 30, 2026

Why Districts?

Paul Rosenzweig

Elections & Political Parties

Jan 30, 2026

Why Districts?

Paul Rosenzweig

Elections & Political Parties

Jan 16, 2026

The Case for Stronger Parties in a Polarized Age

Brandice Canes-Wrone

Elections & Political Parties

Jan 16, 2026

The Case for Stronger Parties in a Polarized Age

Brandice Canes-Wrone

Elections & Political Parties

Jan 16, 2026

The Case for Stronger Parties in a Polarized Age

Brandice Canes-Wrone

Elections & Political Parties

Jan 15, 2026

Democracy Is a Team Sport

Hans Noel

Elections & Political Parties

Jan 15, 2026

Democracy Is a Team Sport

Hans Noel

Elections & Political Parties

Jan 15, 2026

Democracy Is a Team Sport

Hans Noel

Elections & Political Parties