Dec 10, 2025

Building Associational Parties

Tabatha Abu El-Haj

,

Didi Kuo

Dec 10, 2025

Building Associational Parties

Tabatha Abu El-Haj

,

Didi Kuo

Dec 10, 2025

Building Associational Parties

Tabatha Abu El-Haj

,

Didi Kuo

Dec 10, 2025

Building Associational Parties

Tabatha Abu El-Haj

,

Didi Kuo

Dec 10, 2025

Building Associational Parties

Tabatha Abu El-Haj

,

Didi Kuo

Dec 10, 2025

Building Associational Parties

Tabatha Abu El-Haj

,

Didi Kuo

Our political system is failing because our political parties are failing.

Americans want an effective government, but they don’t believe that our political parties can govern well. Wary of politics and cynical about self-serving politicians, a plurality of Americans eschew party labels—a trend particularly pronounced among voters born after 1965. Indeed, in many states, including Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, and North Carolina, independents outnumber partisans on the voter rolls. Their frustration is understandable. But abandoning political parties is not a solution—not if what you want is better governance.

Parties are critical to democratic accountability and policy responsiveness. When critical masses of the population lose faith in parties, it’s not long until they lose faith in democracy itself. Political scientists have long known that young democracies need strong parties. What we are rapidly learning is that even the oldest and wealthiest of modern democracies are fragile when the parties are weak. The problem goes beyond polarization: our parties seem distant and removed from the people they serve, and there are few points of connection that give people the sense that their political engagement makes a meaningful difference in politics. Without a decisive and invested effort in party-building, people will only disengage further from politics—and risk greater contestation over the very meaning of democracy itself.

Abandoning political parties is, therefore, not an option. Democracy and representation require like-minded individuals to work collectively to achieve common goals. Parties are the only associations capable of organizing at scale. They are the only intermediaries that both communicate with voters and govern, and, as such, they are the primary linkage institutions in democracies. Anti-party reforms such as open primaries, non-partisan primaries, and candidate-centric forms of ranked-choice voting leave voters with the mistaken impression that charismatic candidates and political independence are a viable path to the governance and politics they want. Unfortunately, any reform that sidelines political parties is not the answer.

What America needs, instead, are political parties that can build trust and govern effectively. This may require more parties, but it certainly requires better parties. The nationalized and professionalized Democratic and Republican parties that once helmed American democracy have become hollow, personalized, and hopelessly divided. They are not the parties we need. Strengthening their leaders is not a solution: leaders are fleeting, and a party should outlast a single individual. Redirecting the flow of money toward them might improve candidate selection and coherence of the party message, but it cannot be a solution in itself.

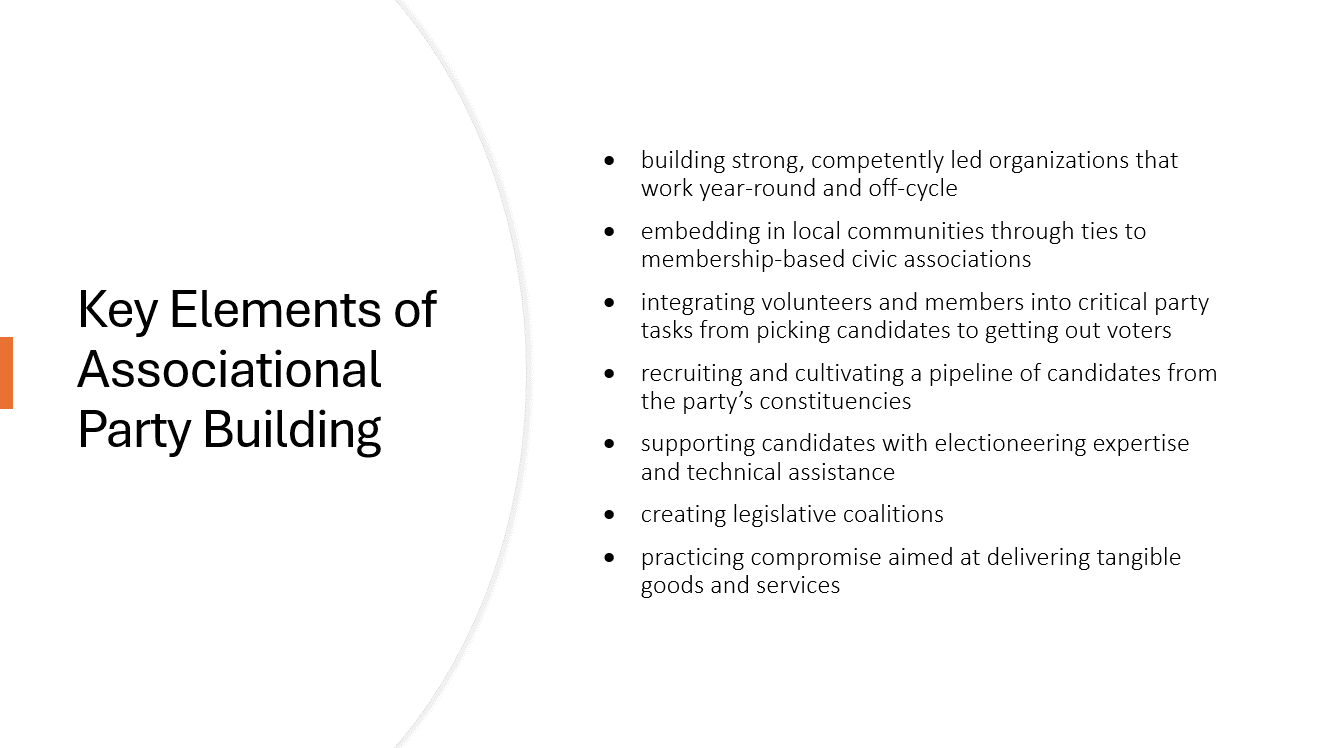

Associational party building is the solution. Restoring Americans’ faith in democracy and in political parties requires engaging in the laborious but necessary process of creating relationships. Associational parties embed themselves in local communities and partner with membership-based civic associations such as churches, unions, and grassroots advocacy groups like the American Legion and Citizen Action. Associational parties invest in party staff and leadership, who recruit and cultivate candidates from the constituencies the party represents. All this work requires investment in an operation that works year-round and off-cycle.

Associational parties understand that winning elected office requires figuring out how to address voter concerns—even disaffection—by devising realistic and responsive policies. But associational parties also engage in a politics of pragmatism, making compromises to deliver tangible goods and services to their voters. They build off local solutions and political victories over the issues that matter most across different communities, including housing, education, infrastructure, and health—even when prioritizing those local concerns does not resonate with the priorities of national donors and political strategists.

Associational parties work to mediate internal party conflict and organize factions in the legislature to fulfill their policy goals, while using their embeddedness to ensure that party elites and agendas do not drift too far from the needs and wants of the people they represent. Through such practice, associational parties link citizens to their government, socializing citizens into politics and providing a consistent mechanism for citizens to have a voice in government.

The idea of associational parties will no doubt seem impossibly idealistic to many, but the fact is that pockets of the Democratic and Republican parties already engage in these key practices. Still, the most successful illustration of associational party-building—as forthcoming research by one of us will show—actually comes from a third party. The Working Families Party (WFP) in New York has used fusion to build a viable, embedded party. Established as a dues-paying party organization, the WFP created not just a brand on the ballot line but a party organization with deep ties to civil society and the electorate through its multiracial coalition of membership organizations. Over the past twenty-five years, it has established itself as a critical player in New York politics. Despite its sharp ideological brand, the WFP routinely engages in strategic compromises to secure tangible outcomes for its supporters, from raising the minimum wage, to repealing the Rockefeller laws, to establishing paid sick leave.

Associational party-building is not a quick fix. It involves hours of knocking on doors and grassroots organizing, as well as the financial investments to sustain that work. But it is possible, and it can bring the responsive governance Americans crave. Indeed, the primary constraint we face in building associational parties is a lack of imagination and a myopic conception of party strength as party leaders‘ control over brand and message. We should consider any reform (including re-legalizing fusion voting) that would incentivize building party organizations as engines of representation, accountability, and broad political participation. But at its core, associational party building requires little more than our commitment to thinking about party strength and spending differently.

Our political system is failing because our political parties are failing.

Americans want an effective government, but they don’t believe that our political parties can govern well. Wary of politics and cynical about self-serving politicians, a plurality of Americans eschew party labels—a trend particularly pronounced among voters born after 1965. Indeed, in many states, including Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, and North Carolina, independents outnumber partisans on the voter rolls. Their frustration is understandable. But abandoning political parties is not a solution—not if what you want is better governance.

Parties are critical to democratic accountability and policy responsiveness. When critical masses of the population lose faith in parties, it’s not long until they lose faith in democracy itself. Political scientists have long known that young democracies need strong parties. What we are rapidly learning is that even the oldest and wealthiest of modern democracies are fragile when the parties are weak. The problem goes beyond polarization: our parties seem distant and removed from the people they serve, and there are few points of connection that give people the sense that their political engagement makes a meaningful difference in politics. Without a decisive and invested effort in party-building, people will only disengage further from politics—and risk greater contestation over the very meaning of democracy itself.

Abandoning political parties is, therefore, not an option. Democracy and representation require like-minded individuals to work collectively to achieve common goals. Parties are the only associations capable of organizing at scale. They are the only intermediaries that both communicate with voters and govern, and, as such, they are the primary linkage institutions in democracies. Anti-party reforms such as open primaries, non-partisan primaries, and candidate-centric forms of ranked-choice voting leave voters with the mistaken impression that charismatic candidates and political independence are a viable path to the governance and politics they want. Unfortunately, any reform that sidelines political parties is not the answer.

What America needs, instead, are political parties that can build trust and govern effectively. This may require more parties, but it certainly requires better parties. The nationalized and professionalized Democratic and Republican parties that once helmed American democracy have become hollow, personalized, and hopelessly divided. They are not the parties we need. Strengthening their leaders is not a solution: leaders are fleeting, and a party should outlast a single individual. Redirecting the flow of money toward them might improve candidate selection and coherence of the party message, but it cannot be a solution in itself.

Associational party building is the solution. Restoring Americans’ faith in democracy and in political parties requires engaging in the laborious but necessary process of creating relationships. Associational parties embed themselves in local communities and partner with membership-based civic associations such as churches, unions, and grassroots advocacy groups like the American Legion and Citizen Action. Associational parties invest in party staff and leadership, who recruit and cultivate candidates from the constituencies the party represents. All this work requires investment in an operation that works year-round and off-cycle.

Associational parties understand that winning elected office requires figuring out how to address voter concerns—even disaffection—by devising realistic and responsive policies. But associational parties also engage in a politics of pragmatism, making compromises to deliver tangible goods and services to their voters. They build off local solutions and political victories over the issues that matter most across different communities, including housing, education, infrastructure, and health—even when prioritizing those local concerns does not resonate with the priorities of national donors and political strategists.

Associational parties work to mediate internal party conflict and organize factions in the legislature to fulfill their policy goals, while using their embeddedness to ensure that party elites and agendas do not drift too far from the needs and wants of the people they represent. Through such practice, associational parties link citizens to their government, socializing citizens into politics and providing a consistent mechanism for citizens to have a voice in government.

The idea of associational parties will no doubt seem impossibly idealistic to many, but the fact is that pockets of the Democratic and Republican parties already engage in these key practices. Still, the most successful illustration of associational party-building—as forthcoming research by one of us will show—actually comes from a third party. The Working Families Party (WFP) in New York has used fusion to build a viable, embedded party. Established as a dues-paying party organization, the WFP created not just a brand on the ballot line but a party organization with deep ties to civil society and the electorate through its multiracial coalition of membership organizations. Over the past twenty-five years, it has established itself as a critical player in New York politics. Despite its sharp ideological brand, the WFP routinely engages in strategic compromises to secure tangible outcomes for its supporters, from raising the minimum wage, to repealing the Rockefeller laws, to establishing paid sick leave.

Associational party-building is not a quick fix. It involves hours of knocking on doors and grassroots organizing, as well as the financial investments to sustain that work. But it is possible, and it can bring the responsive governance Americans crave. Indeed, the primary constraint we face in building associational parties is a lack of imagination and a myopic conception of party strength as party leaders‘ control over brand and message. We should consider any reform (including re-legalizing fusion voting) that would incentivize building party organizations as engines of representation, accountability, and broad political participation. But at its core, associational party building requires little more than our commitment to thinking about party strength and spending differently.

Our political system is failing because our political parties are failing.

Americans want an effective government, but they don’t believe that our political parties can govern well. Wary of politics and cynical about self-serving politicians, a plurality of Americans eschew party labels—a trend particularly pronounced among voters born after 1965. Indeed, in many states, including Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, and North Carolina, independents outnumber partisans on the voter rolls. Their frustration is understandable. But abandoning political parties is not a solution—not if what you want is better governance.

Parties are critical to democratic accountability and policy responsiveness. When critical masses of the population lose faith in parties, it’s not long until they lose faith in democracy itself. Political scientists have long known that young democracies need strong parties. What we are rapidly learning is that even the oldest and wealthiest of modern democracies are fragile when the parties are weak. The problem goes beyond polarization: our parties seem distant and removed from the people they serve, and there are few points of connection that give people the sense that their political engagement makes a meaningful difference in politics. Without a decisive and invested effort in party-building, people will only disengage further from politics—and risk greater contestation over the very meaning of democracy itself.

Abandoning political parties is, therefore, not an option. Democracy and representation require like-minded individuals to work collectively to achieve common goals. Parties are the only associations capable of organizing at scale. They are the only intermediaries that both communicate with voters and govern, and, as such, they are the primary linkage institutions in democracies. Anti-party reforms such as open primaries, non-partisan primaries, and candidate-centric forms of ranked-choice voting leave voters with the mistaken impression that charismatic candidates and political independence are a viable path to the governance and politics they want. Unfortunately, any reform that sidelines political parties is not the answer.

What America needs, instead, are political parties that can build trust and govern effectively. This may require more parties, but it certainly requires better parties. The nationalized and professionalized Democratic and Republican parties that once helmed American democracy have become hollow, personalized, and hopelessly divided. They are not the parties we need. Strengthening their leaders is not a solution: leaders are fleeting, and a party should outlast a single individual. Redirecting the flow of money toward them might improve candidate selection and coherence of the party message, but it cannot be a solution in itself.

Associational party building is the solution. Restoring Americans’ faith in democracy and in political parties requires engaging in the laborious but necessary process of creating relationships. Associational parties embed themselves in local communities and partner with membership-based civic associations such as churches, unions, and grassroots advocacy groups like the American Legion and Citizen Action. Associational parties invest in party staff and leadership, who recruit and cultivate candidates from the constituencies the party represents. All this work requires investment in an operation that works year-round and off-cycle.

Associational parties understand that winning elected office requires figuring out how to address voter concerns—even disaffection—by devising realistic and responsive policies. But associational parties also engage in a politics of pragmatism, making compromises to deliver tangible goods and services to their voters. They build off local solutions and political victories over the issues that matter most across different communities, including housing, education, infrastructure, and health—even when prioritizing those local concerns does not resonate with the priorities of national donors and political strategists.

Associational parties work to mediate internal party conflict and organize factions in the legislature to fulfill their policy goals, while using their embeddedness to ensure that party elites and agendas do not drift too far from the needs and wants of the people they represent. Through such practice, associational parties link citizens to their government, socializing citizens into politics and providing a consistent mechanism for citizens to have a voice in government.

The idea of associational parties will no doubt seem impossibly idealistic to many, but the fact is that pockets of the Democratic and Republican parties already engage in these key practices. Still, the most successful illustration of associational party-building—as forthcoming research by one of us will show—actually comes from a third party. The Working Families Party (WFP) in New York has used fusion to build a viable, embedded party. Established as a dues-paying party organization, the WFP created not just a brand on the ballot line but a party organization with deep ties to civil society and the electorate through its multiracial coalition of membership organizations. Over the past twenty-five years, it has established itself as a critical player in New York politics. Despite its sharp ideological brand, the WFP routinely engages in strategic compromises to secure tangible outcomes for its supporters, from raising the minimum wage, to repealing the Rockefeller laws, to establishing paid sick leave.

Associational party-building is not a quick fix. It involves hours of knocking on doors and grassroots organizing, as well as the financial investments to sustain that work. But it is possible, and it can bring the responsive governance Americans crave. Indeed, the primary constraint we face in building associational parties is a lack of imagination and a myopic conception of party strength as party leaders‘ control over brand and message. We should consider any reform (including re-legalizing fusion voting) that would incentivize building party organizations as engines of representation, accountability, and broad political participation. But at its core, associational party building requires little more than our commitment to thinking about party strength and spending differently.

Our political system is failing because our political parties are failing.

Americans want an effective government, but they don’t believe that our political parties can govern well. Wary of politics and cynical about self-serving politicians, a plurality of Americans eschew party labels—a trend particularly pronounced among voters born after 1965. Indeed, in many states, including Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, and North Carolina, independents outnumber partisans on the voter rolls. Their frustration is understandable. But abandoning political parties is not a solution—not if what you want is better governance.

Parties are critical to democratic accountability and policy responsiveness. When critical masses of the population lose faith in parties, it’s not long until they lose faith in democracy itself. Political scientists have long known that young democracies need strong parties. What we are rapidly learning is that even the oldest and wealthiest of modern democracies are fragile when the parties are weak. The problem goes beyond polarization: our parties seem distant and removed from the people they serve, and there are few points of connection that give people the sense that their political engagement makes a meaningful difference in politics. Without a decisive and invested effort in party-building, people will only disengage further from politics—and risk greater contestation over the very meaning of democracy itself.

Abandoning political parties is, therefore, not an option. Democracy and representation require like-minded individuals to work collectively to achieve common goals. Parties are the only associations capable of organizing at scale. They are the only intermediaries that both communicate with voters and govern, and, as such, they are the primary linkage institutions in democracies. Anti-party reforms such as open primaries, non-partisan primaries, and candidate-centric forms of ranked-choice voting leave voters with the mistaken impression that charismatic candidates and political independence are a viable path to the governance and politics they want. Unfortunately, any reform that sidelines political parties is not the answer.

What America needs, instead, are political parties that can build trust and govern effectively. This may require more parties, but it certainly requires better parties. The nationalized and professionalized Democratic and Republican parties that once helmed American democracy have become hollow, personalized, and hopelessly divided. They are not the parties we need. Strengthening their leaders is not a solution: leaders are fleeting, and a party should outlast a single individual. Redirecting the flow of money toward them might improve candidate selection and coherence of the party message, but it cannot be a solution in itself.

Associational party building is the solution. Restoring Americans’ faith in democracy and in political parties requires engaging in the laborious but necessary process of creating relationships. Associational parties embed themselves in local communities and partner with membership-based civic associations such as churches, unions, and grassroots advocacy groups like the American Legion and Citizen Action. Associational parties invest in party staff and leadership, who recruit and cultivate candidates from the constituencies the party represents. All this work requires investment in an operation that works year-round and off-cycle.

Associational parties understand that winning elected office requires figuring out how to address voter concerns—even disaffection—by devising realistic and responsive policies. But associational parties also engage in a politics of pragmatism, making compromises to deliver tangible goods and services to their voters. They build off local solutions and political victories over the issues that matter most across different communities, including housing, education, infrastructure, and health—even when prioritizing those local concerns does not resonate with the priorities of national donors and political strategists.

Associational parties work to mediate internal party conflict and organize factions in the legislature to fulfill their policy goals, while using their embeddedness to ensure that party elites and agendas do not drift too far from the needs and wants of the people they represent. Through such practice, associational parties link citizens to their government, socializing citizens into politics and providing a consistent mechanism for citizens to have a voice in government.

The idea of associational parties will no doubt seem impossibly idealistic to many, but the fact is that pockets of the Democratic and Republican parties already engage in these key practices. Still, the most successful illustration of associational party-building—as forthcoming research by one of us will show—actually comes from a third party. The Working Families Party (WFP) in New York has used fusion to build a viable, embedded party. Established as a dues-paying party organization, the WFP created not just a brand on the ballot line but a party organization with deep ties to civil society and the electorate through its multiracial coalition of membership organizations. Over the past twenty-five years, it has established itself as a critical player in New York politics. Despite its sharp ideological brand, the WFP routinely engages in strategic compromises to secure tangible outcomes for its supporters, from raising the minimum wage, to repealing the Rockefeller laws, to establishing paid sick leave.

Associational party-building is not a quick fix. It involves hours of knocking on doors and grassroots organizing, as well as the financial investments to sustain that work. But it is possible, and it can bring the responsive governance Americans crave. Indeed, the primary constraint we face in building associational parties is a lack of imagination and a myopic conception of party strength as party leaders‘ control over brand and message. We should consider any reform (including re-legalizing fusion voting) that would incentivize building party organizations as engines of representation, accountability, and broad political participation. But at its core, associational party building requires little more than our commitment to thinking about party strength and spending differently.

Our political system is failing because our political parties are failing.

Americans want an effective government, but they don’t believe that our political parties can govern well. Wary of politics and cynical about self-serving politicians, a plurality of Americans eschew party labels—a trend particularly pronounced among voters born after 1965. Indeed, in many states, including Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, and North Carolina, independents outnumber partisans on the voter rolls. Their frustration is understandable. But abandoning political parties is not a solution—not if what you want is better governance.

Parties are critical to democratic accountability and policy responsiveness. When critical masses of the population lose faith in parties, it’s not long until they lose faith in democracy itself. Political scientists have long known that young democracies need strong parties. What we are rapidly learning is that even the oldest and wealthiest of modern democracies are fragile when the parties are weak. The problem goes beyond polarization: our parties seem distant and removed from the people they serve, and there are few points of connection that give people the sense that their political engagement makes a meaningful difference in politics. Without a decisive and invested effort in party-building, people will only disengage further from politics—and risk greater contestation over the very meaning of democracy itself.

Abandoning political parties is, therefore, not an option. Democracy and representation require like-minded individuals to work collectively to achieve common goals. Parties are the only associations capable of organizing at scale. They are the only intermediaries that both communicate with voters and govern, and, as such, they are the primary linkage institutions in democracies. Anti-party reforms such as open primaries, non-partisan primaries, and candidate-centric forms of ranked-choice voting leave voters with the mistaken impression that charismatic candidates and political independence are a viable path to the governance and politics they want. Unfortunately, any reform that sidelines political parties is not the answer.

What America needs, instead, are political parties that can build trust and govern effectively. This may require more parties, but it certainly requires better parties. The nationalized and professionalized Democratic and Republican parties that once helmed American democracy have become hollow, personalized, and hopelessly divided. They are not the parties we need. Strengthening their leaders is not a solution: leaders are fleeting, and a party should outlast a single individual. Redirecting the flow of money toward them might improve candidate selection and coherence of the party message, but it cannot be a solution in itself.

Associational party building is the solution. Restoring Americans’ faith in democracy and in political parties requires engaging in the laborious but necessary process of creating relationships. Associational parties embed themselves in local communities and partner with membership-based civic associations such as churches, unions, and grassroots advocacy groups like the American Legion and Citizen Action. Associational parties invest in party staff and leadership, who recruit and cultivate candidates from the constituencies the party represents. All this work requires investment in an operation that works year-round and off-cycle.

Associational parties understand that winning elected office requires figuring out how to address voter concerns—even disaffection—by devising realistic and responsive policies. But associational parties also engage in a politics of pragmatism, making compromises to deliver tangible goods and services to their voters. They build off local solutions and political victories over the issues that matter most across different communities, including housing, education, infrastructure, and health—even when prioritizing those local concerns does not resonate with the priorities of national donors and political strategists.

Associational parties work to mediate internal party conflict and organize factions in the legislature to fulfill their policy goals, while using their embeddedness to ensure that party elites and agendas do not drift too far from the needs and wants of the people they represent. Through such practice, associational parties link citizens to their government, socializing citizens into politics and providing a consistent mechanism for citizens to have a voice in government.

The idea of associational parties will no doubt seem impossibly idealistic to many, but the fact is that pockets of the Democratic and Republican parties already engage in these key practices. Still, the most successful illustration of associational party-building—as forthcoming research by one of us will show—actually comes from a third party. The Working Families Party (WFP) in New York has used fusion to build a viable, embedded party. Established as a dues-paying party organization, the WFP created not just a brand on the ballot line but a party organization with deep ties to civil society and the electorate through its multiracial coalition of membership organizations. Over the past twenty-five years, it has established itself as a critical player in New York politics. Despite its sharp ideological brand, the WFP routinely engages in strategic compromises to secure tangible outcomes for its supporters, from raising the minimum wage, to repealing the Rockefeller laws, to establishing paid sick leave.

Associational party-building is not a quick fix. It involves hours of knocking on doors and grassroots organizing, as well as the financial investments to sustain that work. But it is possible, and it can bring the responsive governance Americans crave. Indeed, the primary constraint we face in building associational parties is a lack of imagination and a myopic conception of party strength as party leaders‘ control over brand and message. We should consider any reform (including re-legalizing fusion voting) that would incentivize building party organizations as engines of representation, accountability, and broad political participation. But at its core, associational party building requires little more than our commitment to thinking about party strength and spending differently.

Our political system is failing because our political parties are failing.

Americans want an effective government, but they don’t believe that our political parties can govern well. Wary of politics and cynical about self-serving politicians, a plurality of Americans eschew party labels—a trend particularly pronounced among voters born after 1965. Indeed, in many states, including Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, and North Carolina, independents outnumber partisans on the voter rolls. Their frustration is understandable. But abandoning political parties is not a solution—not if what you want is better governance.

Parties are critical to democratic accountability and policy responsiveness. When critical masses of the population lose faith in parties, it’s not long until they lose faith in democracy itself. Political scientists have long known that young democracies need strong parties. What we are rapidly learning is that even the oldest and wealthiest of modern democracies are fragile when the parties are weak. The problem goes beyond polarization: our parties seem distant and removed from the people they serve, and there are few points of connection that give people the sense that their political engagement makes a meaningful difference in politics. Without a decisive and invested effort in party-building, people will only disengage further from politics—and risk greater contestation over the very meaning of democracy itself.

Abandoning political parties is, therefore, not an option. Democracy and representation require like-minded individuals to work collectively to achieve common goals. Parties are the only associations capable of organizing at scale. They are the only intermediaries that both communicate with voters and govern, and, as such, they are the primary linkage institutions in democracies. Anti-party reforms such as open primaries, non-partisan primaries, and candidate-centric forms of ranked-choice voting leave voters with the mistaken impression that charismatic candidates and political independence are a viable path to the governance and politics they want. Unfortunately, any reform that sidelines political parties is not the answer.

What America needs, instead, are political parties that can build trust and govern effectively. This may require more parties, but it certainly requires better parties. The nationalized and professionalized Democratic and Republican parties that once helmed American democracy have become hollow, personalized, and hopelessly divided. They are not the parties we need. Strengthening their leaders is not a solution: leaders are fleeting, and a party should outlast a single individual. Redirecting the flow of money toward them might improve candidate selection and coherence of the party message, but it cannot be a solution in itself.

Associational party building is the solution. Restoring Americans’ faith in democracy and in political parties requires engaging in the laborious but necessary process of creating relationships. Associational parties embed themselves in local communities and partner with membership-based civic associations such as churches, unions, and grassroots advocacy groups like the American Legion and Citizen Action. Associational parties invest in party staff and leadership, who recruit and cultivate candidates from the constituencies the party represents. All this work requires investment in an operation that works year-round and off-cycle.

Associational parties understand that winning elected office requires figuring out how to address voter concerns—even disaffection—by devising realistic and responsive policies. But associational parties also engage in a politics of pragmatism, making compromises to deliver tangible goods and services to their voters. They build off local solutions and political victories over the issues that matter most across different communities, including housing, education, infrastructure, and health—even when prioritizing those local concerns does not resonate with the priorities of national donors and political strategists.

Associational parties work to mediate internal party conflict and organize factions in the legislature to fulfill their policy goals, while using their embeddedness to ensure that party elites and agendas do not drift too far from the needs and wants of the people they represent. Through such practice, associational parties link citizens to their government, socializing citizens into politics and providing a consistent mechanism for citizens to have a voice in government.

The idea of associational parties will no doubt seem impossibly idealistic to many, but the fact is that pockets of the Democratic and Republican parties already engage in these key practices. Still, the most successful illustration of associational party-building—as forthcoming research by one of us will show—actually comes from a third party. The Working Families Party (WFP) in New York has used fusion to build a viable, embedded party. Established as a dues-paying party organization, the WFP created not just a brand on the ballot line but a party organization with deep ties to civil society and the electorate through its multiracial coalition of membership organizations. Over the past twenty-five years, it has established itself as a critical player in New York politics. Despite its sharp ideological brand, the WFP routinely engages in strategic compromises to secure tangible outcomes for its supporters, from raising the minimum wage, to repealing the Rockefeller laws, to establishing paid sick leave.

Associational party-building is not a quick fix. It involves hours of knocking on doors and grassroots organizing, as well as the financial investments to sustain that work. But it is possible, and it can bring the responsive governance Americans crave. Indeed, the primary constraint we face in building associational parties is a lack of imagination and a myopic conception of party strength as party leaders‘ control over brand and message. We should consider any reform (including re-legalizing fusion voting) that would incentivize building party organizations as engines of representation, accountability, and broad political participation. But at its core, associational party building requires little more than our commitment to thinking about party strength and spending differently.

About the Author

Tabatha Abu El-Haj

Tabatha Abu El-Haj is a Professor of Law at Drexel University’s Thomas R. Kline School of Law. An expert on the First Amendment and the law of democracy, her publications include “Changing the People: Legal Regulation and American Democracy” (NYU Law Review vol. 86(1) 2011), “Networking the Party: First Amendment Rights & the Pursuit of Responsive Party Government” (Columbia Law Review vol. 118(4) 2019), and most recently “Associational Party-Building: A Path to Rebuilding Democracy,” (coauthored with Didi Kuo, Columbia Law Review Forum vol. 122(7) 2022).

About the Author

Tabatha Abu El-Haj

Tabatha Abu El-Haj is a Professor of Law at Drexel University’s Thomas R. Kline School of Law. An expert on the First Amendment and the law of democracy, her publications include “Changing the People: Legal Regulation and American Democracy” (NYU Law Review vol. 86(1) 2011), “Networking the Party: First Amendment Rights & the Pursuit of Responsive Party Government” (Columbia Law Review vol. 118(4) 2019), and most recently “Associational Party-Building: A Path to Rebuilding Democracy,” (coauthored with Didi Kuo, Columbia Law Review Forum vol. 122(7) 2022).

About the Author

Tabatha Abu El-Haj

Tabatha Abu El-Haj is a Professor of Law at Drexel University’s Thomas R. Kline School of Law. An expert on the First Amendment and the law of democracy, her publications include “Changing the People: Legal Regulation and American Democracy” (NYU Law Review vol. 86(1) 2011), “Networking the Party: First Amendment Rights & the Pursuit of Responsive Party Government” (Columbia Law Review vol. 118(4) 2019), and most recently “Associational Party-Building: A Path to Rebuilding Democracy,” (coauthored with Didi Kuo, Columbia Law Review Forum vol. 122(7) 2022).

About the Author

Didi Kuo

Kuo is a Center Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) at Stanford University. She is a scholar of comparative politics with a focus on democratization, corruption and clientelism, political parties and institutions, and political reform. She is the author of "The Great Retreat: How Political Parties Should Behave and Why They Don’t" (Oxford University Press, 2025) and "Clientelism, Capitalism, and Democracy: The Rise of Programmatic Politics in the United States and Britain" (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

About the Author

Didi Kuo

Kuo is a Center Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) at Stanford University. She is a scholar of comparative politics with a focus on democratization, corruption and clientelism, political parties and institutions, and political reform. She is the author of "The Great Retreat: How Political Parties Should Behave and Why They Don’t" (Oxford University Press, 2025) and "Clientelism, Capitalism, and Democracy: The Rise of Programmatic Politics in the United States and Britain" (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

About the Author

Didi Kuo

Kuo is a Center Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) at Stanford University. She is a scholar of comparative politics with a focus on democratization, corruption and clientelism, political parties and institutions, and political reform. She is the author of "The Great Retreat: How Political Parties Should Behave and Why They Don’t" (Oxford University Press, 2025) and "Clientelism, Capitalism, and Democracy: The Rise of Programmatic Politics in the United States and Britain" (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

More viewpoints in

Elections & Political Parties

Mar 10, 2026

The Slender Reed of "Norms"

Fred Martin

Elections & Political Parties

Mar 10, 2026

The Slender Reed of "Norms"

Fred Martin

Elections & Political Parties

Mar 10, 2026

The Slender Reed of "Norms"

Fred Martin

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 18, 2026

Strengthen Democracy by Empowering People to Vote with their Feet

Ilya Somin

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 18, 2026

Strengthen Democracy by Empowering People to Vote with their Feet

Ilya Somin

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 18, 2026

Strengthen Democracy by Empowering People to Vote with their Feet

Ilya Somin

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 10, 2026

Montana Responded to Citizens United. Here’s What We Learned.

Steve Bullock

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 10, 2026

Montana Responded to Citizens United. Here’s What We Learned.

Steve Bullock

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 10, 2026

Montana Responded to Citizens United. Here’s What We Learned.

Steve Bullock

Elections & Political Parties

More viewpoints in

Elections & Political Parties

Mar 10, 2026

The Slender Reed of "Norms"

Fred Martin

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 18, 2026

Strengthen Democracy by Empowering People to Vote with their Feet

Ilya Somin

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 10, 2026

Montana Responded to Citizens United. Here’s What We Learned.

Steve Bullock

Elections & Political Parties

More viewpoints in

Elections & Political Parties

Mar 10, 2026

The Slender Reed of "Norms"

Fred Martin

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 18, 2026

Strengthen Democracy by Empowering People to Vote with their Feet

Ilya Somin

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 10, 2026

Montana Responded to Citizens United. Here’s What We Learned.

Steve Bullock

Elections & Political Parties

More viewpoints in

Elections & Political Parties

Mar 10, 2026

The Slender Reed of "Norms"

Fred Martin

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 18, 2026

Strengthen Democracy by Empowering People to Vote with their Feet

Ilya Somin

Elections & Political Parties

Feb 10, 2026

Montana Responded to Citizens United. Here’s What We Learned.

Steve Bullock

Elections & Political Parties