Oct 31, 2025

The Threat to Government Ethics

Richard Briffault

Oct 31, 2025

The Threat to Government Ethics

Richard Briffault

Oct 31, 2025

The Threat to Government Ethics

Richard Briffault

Oct 31, 2025

The Threat to Government Ethics

Richard Briffault

Oct 31, 2025

The Threat to Government Ethics

Richard Briffault

Oct 31, 2025

The Threat to Government Ethics

Richard Briffault

That was quite a week. Over seven days in mid-October,

President Trump hosted a White House dinner for three dozen super-wealthy individuals and representatives of major corporations who pledged funds for his $300 million ballroom.

The president commuted the sentence of former Congressman George Santos, who had served less than three months of an 87-month term for corruption, and canceled Santos’s obligation to pay restitution to his victims.

The president fired, without providing a reason or giving the 30 days’ notice required by law, the Inspector General for the Export-Import Bank.

We learned the president is demanding the Department of Justice pay him $230 million in compensation for federal investigations into his alleged misconduct while a private citizen.

The president pardoned Changpeng Zhao, the billionaire founder of the cryptocurrency exchange Binance, who had previously pleaded guilty to money laundering violations. Binance is a business partner of World Liberty Financial, the crypto venture launched last year by the Trump family.

These developments, each significant in its own right, are but a microcosm of the Trump administration’s broader, two-pronged attack on the ethics foundation of our democracy – the dismantling of the federal ethics structure, coupled with Trump’s unprecedented use of presidential power and influence for private financial gain.

On the structural side, over the last nine months the president fired multiple anti-corruption watchdogs, including the heads of the Office of Government Ethics and the Office of Special Counsel and two dozen Inspectors General. The Department of Justice reduced enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the Foreign Agents Registration Act, gutted its Public Integrity Unit, and dismissed the director of its ethics office; the FBI disbanded its public corruption squad. Trump repeatedly pardoned federal, state, and local officials convicted of public corruption, as well as a host of private fraudsters, thereby undermining the future deterrent effect of federal anti-corruption law.

On the private side, Trump continued his first-term practice of using official meetings and events to promote his private properties. But he has broken new ground in using the power and prestige of the presidency for personal gain by offering White House tours to the individuals who bought the most $TRUMP meme coin; obtaining multimillion-dollar settlements of the libel suits he had brought against media companies that are subject to federal regulation; and securing a $400 million jet from Qatar, which will become property of his foundation when he leaves office. So, too, the Trump family crypto firm has been enriched by transactions with entities, foreign and domestic, that have a stake in U.S. government decisions.

To be sure, President Trump is not the only ethically challenged actor in Washington. Some members of Congress, after an early briefing on the likely impact of COVID on the economy, traded stocks on that information; others continue to trade in stocks of firms influenced by the committees on which they sit. Justices of the Supreme Court have drawn critical scrutiny for accepting, and not disclosing, gifts of luxury travel.

But the president’s destruction of ethics institutions and use of office for private pecuniary benefit are unique in scope and effect.

In our representative democracy, the people we elect to office, and those they appoint, are there to serve the public, not themselves. Henry Clay said it well: “Government is a trust, and the officers of the government are trustees; and both the trust and the trustees are created for the benefit of the people,” not the officeholders. Congress has similarly resolved that any person on government should “never accept, for himself or his family, favors or benefits under circumstances which might be construed by reasonable persons as influencing the performance of his governmental duties.”

This is not just a matter of abstract idealistic theorizing. When public office and private interest are intertwined, it becomes impossible to determine the basis of government decisions. Are crypto-friendly government actions grounded in sound policy judgments or the Trump family’s financial interests? Are the administration’s deals with Persian Gulf potentates based on national security or pecuniary self-interest? Can our leaders even tell public and private reasons apart when public and private interests are so blended?

A fish rots from the head down. By bulldozing the ethics guardrails and demonstrating a blatant disregard for conflicts of interest, the president has effectively given a green light to self-interested behavior throughout the government. Such corruption inevitably results in inefficient and unequally provided public services and regulation, with long-term consequences for government effectiveness, and for the public trust essential for democracy to function.

What can be done? Currently, most federal conflicts of interest laws do not apply to the president. There are constitutional issues beyond the scope of this essay as to how far Congress can go but those issues would be worth testing with restrictions targeted on the financial holdings of the president and immediate family members in firms subject to federal oversight or regulation.

An even tougher issue is enforcement. With the DOJ run by Trump loyalists, any enforcement of ethics rules today would be based on the president’s personal interests, not the rules themselves. Some states have adopted independent ethics enforcement institutions, with commissioners appointed by different elected officials and serving for fixed terms, and protected from removal. The Supreme Court’s deepening embrace of the unitary executive theory makes it hard to imagine that a similar federal independent ethics agency could pass constitutional muster. But, as with the substantive restrictions, the constitutional issues are worth testing, and Congress should consider creating an independent, protected ethics watchdog, with enhanced investigative, if not enforcement, authority.

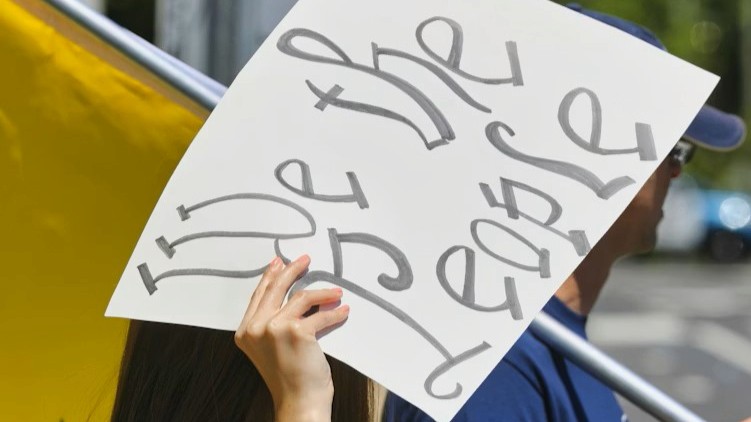

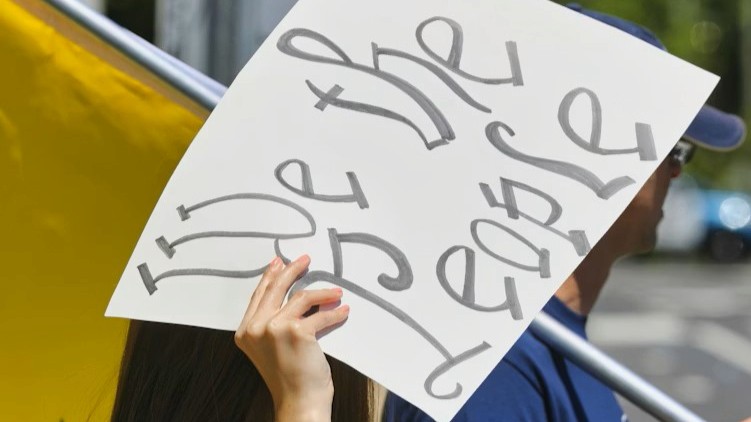

Ultimately, any vindication of the public trust principle will depend on the people. As Madison asked, “Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation.” The last episode of major presidential misconduct – Watergate – led to political and legal reactions that improved the ethical climate, at least for a time. We can hope, and strive for, a similar response this time.

That was quite a week. Over seven days in mid-October,

President Trump hosted a White House dinner for three dozen super-wealthy individuals and representatives of major corporations who pledged funds for his $300 million ballroom.

The president commuted the sentence of former Congressman George Santos, who had served less than three months of an 87-month term for corruption, and canceled Santos’s obligation to pay restitution to his victims.

The president fired, without providing a reason or giving the 30 days’ notice required by law, the Inspector General for the Export-Import Bank.

We learned the president is demanding the Department of Justice pay him $230 million in compensation for federal investigations into his alleged misconduct while a private citizen.

The president pardoned Changpeng Zhao, the billionaire founder of the cryptocurrency exchange Binance, who had previously pleaded guilty to money laundering violations. Binance is a business partner of World Liberty Financial, the crypto venture launched last year by the Trump family.

These developments, each significant in its own right, are but a microcosm of the Trump administration’s broader, two-pronged attack on the ethics foundation of our democracy – the dismantling of the federal ethics structure, coupled with Trump’s unprecedented use of presidential power and influence for private financial gain.

On the structural side, over the last nine months the president fired multiple anti-corruption watchdogs, including the heads of the Office of Government Ethics and the Office of Special Counsel and two dozen Inspectors General. The Department of Justice reduced enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the Foreign Agents Registration Act, gutted its Public Integrity Unit, and dismissed the director of its ethics office; the FBI disbanded its public corruption squad. Trump repeatedly pardoned federal, state, and local officials convicted of public corruption, as well as a host of private fraudsters, thereby undermining the future deterrent effect of federal anti-corruption law.

On the private side, Trump continued his first-term practice of using official meetings and events to promote his private properties. But he has broken new ground in using the power and prestige of the presidency for personal gain by offering White House tours to the individuals who bought the most $TRUMP meme coin; obtaining multimillion-dollar settlements of the libel suits he had brought against media companies that are subject to federal regulation; and securing a $400 million jet from Qatar, which will become property of his foundation when he leaves office. So, too, the Trump family crypto firm has been enriched by transactions with entities, foreign and domestic, that have a stake in U.S. government decisions.

To be sure, President Trump is not the only ethically challenged actor in Washington. Some members of Congress, after an early briefing on the likely impact of COVID on the economy, traded stocks on that information; others continue to trade in stocks of firms influenced by the committees on which they sit. Justices of the Supreme Court have drawn critical scrutiny for accepting, and not disclosing, gifts of luxury travel.

But the president’s destruction of ethics institutions and use of office for private pecuniary benefit are unique in scope and effect.

In our representative democracy, the people we elect to office, and those they appoint, are there to serve the public, not themselves. Henry Clay said it well: “Government is a trust, and the officers of the government are trustees; and both the trust and the trustees are created for the benefit of the people,” not the officeholders. Congress has similarly resolved that any person on government should “never accept, for himself or his family, favors or benefits under circumstances which might be construed by reasonable persons as influencing the performance of his governmental duties.”

This is not just a matter of abstract idealistic theorizing. When public office and private interest are intertwined, it becomes impossible to determine the basis of government decisions. Are crypto-friendly government actions grounded in sound policy judgments or the Trump family’s financial interests? Are the administration’s deals with Persian Gulf potentates based on national security or pecuniary self-interest? Can our leaders even tell public and private reasons apart when public and private interests are so blended?

A fish rots from the head down. By bulldozing the ethics guardrails and demonstrating a blatant disregard for conflicts of interest, the president has effectively given a green light to self-interested behavior throughout the government. Such corruption inevitably results in inefficient and unequally provided public services and regulation, with long-term consequences for government effectiveness, and for the public trust essential for democracy to function.

What can be done? Currently, most federal conflicts of interest laws do not apply to the president. There are constitutional issues beyond the scope of this essay as to how far Congress can go but those issues would be worth testing with restrictions targeted on the financial holdings of the president and immediate family members in firms subject to federal oversight or regulation.

An even tougher issue is enforcement. With the DOJ run by Trump loyalists, any enforcement of ethics rules today would be based on the president’s personal interests, not the rules themselves. Some states have adopted independent ethics enforcement institutions, with commissioners appointed by different elected officials and serving for fixed terms, and protected from removal. The Supreme Court’s deepening embrace of the unitary executive theory makes it hard to imagine that a similar federal independent ethics agency could pass constitutional muster. But, as with the substantive restrictions, the constitutional issues are worth testing, and Congress should consider creating an independent, protected ethics watchdog, with enhanced investigative, if not enforcement, authority.

Ultimately, any vindication of the public trust principle will depend on the people. As Madison asked, “Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation.” The last episode of major presidential misconduct – Watergate – led to political and legal reactions that improved the ethical climate, at least for a time. We can hope, and strive for, a similar response this time.

That was quite a week. Over seven days in mid-October,

President Trump hosted a White House dinner for three dozen super-wealthy individuals and representatives of major corporations who pledged funds for his $300 million ballroom.

The president commuted the sentence of former Congressman George Santos, who had served less than three months of an 87-month term for corruption, and canceled Santos’s obligation to pay restitution to his victims.

The president fired, without providing a reason or giving the 30 days’ notice required by law, the Inspector General for the Export-Import Bank.

We learned the president is demanding the Department of Justice pay him $230 million in compensation for federal investigations into his alleged misconduct while a private citizen.

The president pardoned Changpeng Zhao, the billionaire founder of the cryptocurrency exchange Binance, who had previously pleaded guilty to money laundering violations. Binance is a business partner of World Liberty Financial, the crypto venture launched last year by the Trump family.

These developments, each significant in its own right, are but a microcosm of the Trump administration’s broader, two-pronged attack on the ethics foundation of our democracy – the dismantling of the federal ethics structure, coupled with Trump’s unprecedented use of presidential power and influence for private financial gain.

On the structural side, over the last nine months the president fired multiple anti-corruption watchdogs, including the heads of the Office of Government Ethics and the Office of Special Counsel and two dozen Inspectors General. The Department of Justice reduced enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the Foreign Agents Registration Act, gutted its Public Integrity Unit, and dismissed the director of its ethics office; the FBI disbanded its public corruption squad. Trump repeatedly pardoned federal, state, and local officials convicted of public corruption, as well as a host of private fraudsters, thereby undermining the future deterrent effect of federal anti-corruption law.

On the private side, Trump continued his first-term practice of using official meetings and events to promote his private properties. But he has broken new ground in using the power and prestige of the presidency for personal gain by offering White House tours to the individuals who bought the most $TRUMP meme coin; obtaining multimillion-dollar settlements of the libel suits he had brought against media companies that are subject to federal regulation; and securing a $400 million jet from Qatar, which will become property of his foundation when he leaves office. So, too, the Trump family crypto firm has been enriched by transactions with entities, foreign and domestic, that have a stake in U.S. government decisions.

To be sure, President Trump is not the only ethically challenged actor in Washington. Some members of Congress, after an early briefing on the likely impact of COVID on the economy, traded stocks on that information; others continue to trade in stocks of firms influenced by the committees on which they sit. Justices of the Supreme Court have drawn critical scrutiny for accepting, and not disclosing, gifts of luxury travel.

But the president’s destruction of ethics institutions and use of office for private pecuniary benefit are unique in scope and effect.

In our representative democracy, the people we elect to office, and those they appoint, are there to serve the public, not themselves. Henry Clay said it well: “Government is a trust, and the officers of the government are trustees; and both the trust and the trustees are created for the benefit of the people,” not the officeholders. Congress has similarly resolved that any person on government should “never accept, for himself or his family, favors or benefits under circumstances which might be construed by reasonable persons as influencing the performance of his governmental duties.”

This is not just a matter of abstract idealistic theorizing. When public office and private interest are intertwined, it becomes impossible to determine the basis of government decisions. Are crypto-friendly government actions grounded in sound policy judgments or the Trump family’s financial interests? Are the administration’s deals with Persian Gulf potentates based on national security or pecuniary self-interest? Can our leaders even tell public and private reasons apart when public and private interests are so blended?

A fish rots from the head down. By bulldozing the ethics guardrails and demonstrating a blatant disregard for conflicts of interest, the president has effectively given a green light to self-interested behavior throughout the government. Such corruption inevitably results in inefficient and unequally provided public services and regulation, with long-term consequences for government effectiveness, and for the public trust essential for democracy to function.

What can be done? Currently, most federal conflicts of interest laws do not apply to the president. There are constitutional issues beyond the scope of this essay as to how far Congress can go but those issues would be worth testing with restrictions targeted on the financial holdings of the president and immediate family members in firms subject to federal oversight or regulation.

An even tougher issue is enforcement. With the DOJ run by Trump loyalists, any enforcement of ethics rules today would be based on the president’s personal interests, not the rules themselves. Some states have adopted independent ethics enforcement institutions, with commissioners appointed by different elected officials and serving for fixed terms, and protected from removal. The Supreme Court’s deepening embrace of the unitary executive theory makes it hard to imagine that a similar federal independent ethics agency could pass constitutional muster. But, as with the substantive restrictions, the constitutional issues are worth testing, and Congress should consider creating an independent, protected ethics watchdog, with enhanced investigative, if not enforcement, authority.

Ultimately, any vindication of the public trust principle will depend on the people. As Madison asked, “Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation.” The last episode of major presidential misconduct – Watergate – led to political and legal reactions that improved the ethical climate, at least for a time. We can hope, and strive for, a similar response this time.

That was quite a week. Over seven days in mid-October,

President Trump hosted a White House dinner for three dozen super-wealthy individuals and representatives of major corporations who pledged funds for his $300 million ballroom.

The president commuted the sentence of former Congressman George Santos, who had served less than three months of an 87-month term for corruption, and canceled Santos’s obligation to pay restitution to his victims.

The president fired, without providing a reason or giving the 30 days’ notice required by law, the Inspector General for the Export-Import Bank.

We learned the president is demanding the Department of Justice pay him $230 million in compensation for federal investigations into his alleged misconduct while a private citizen.

The president pardoned Changpeng Zhao, the billionaire founder of the cryptocurrency exchange Binance, who had previously pleaded guilty to money laundering violations. Binance is a business partner of World Liberty Financial, the crypto venture launched last year by the Trump family.

These developments, each significant in its own right, are but a microcosm of the Trump administration’s broader, two-pronged attack on the ethics foundation of our democracy – the dismantling of the federal ethics structure, coupled with Trump’s unprecedented use of presidential power and influence for private financial gain.

On the structural side, over the last nine months the president fired multiple anti-corruption watchdogs, including the heads of the Office of Government Ethics and the Office of Special Counsel and two dozen Inspectors General. The Department of Justice reduced enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the Foreign Agents Registration Act, gutted its Public Integrity Unit, and dismissed the director of its ethics office; the FBI disbanded its public corruption squad. Trump repeatedly pardoned federal, state, and local officials convicted of public corruption, as well as a host of private fraudsters, thereby undermining the future deterrent effect of federal anti-corruption law.

On the private side, Trump continued his first-term practice of using official meetings and events to promote his private properties. But he has broken new ground in using the power and prestige of the presidency for personal gain by offering White House tours to the individuals who bought the most $TRUMP meme coin; obtaining multimillion-dollar settlements of the libel suits he had brought against media companies that are subject to federal regulation; and securing a $400 million jet from Qatar, which will become property of his foundation when he leaves office. So, too, the Trump family crypto firm has been enriched by transactions with entities, foreign and domestic, that have a stake in U.S. government decisions.

To be sure, President Trump is not the only ethically challenged actor in Washington. Some members of Congress, after an early briefing on the likely impact of COVID on the economy, traded stocks on that information; others continue to trade in stocks of firms influenced by the committees on which they sit. Justices of the Supreme Court have drawn critical scrutiny for accepting, and not disclosing, gifts of luxury travel.

But the president’s destruction of ethics institutions and use of office for private pecuniary benefit are unique in scope and effect.

In our representative democracy, the people we elect to office, and those they appoint, are there to serve the public, not themselves. Henry Clay said it well: “Government is a trust, and the officers of the government are trustees; and both the trust and the trustees are created for the benefit of the people,” not the officeholders. Congress has similarly resolved that any person on government should “never accept, for himself or his family, favors or benefits under circumstances which might be construed by reasonable persons as influencing the performance of his governmental duties.”

This is not just a matter of abstract idealistic theorizing. When public office and private interest are intertwined, it becomes impossible to determine the basis of government decisions. Are crypto-friendly government actions grounded in sound policy judgments or the Trump family’s financial interests? Are the administration’s deals with Persian Gulf potentates based on national security or pecuniary self-interest? Can our leaders even tell public and private reasons apart when public and private interests are so blended?

A fish rots from the head down. By bulldozing the ethics guardrails and demonstrating a blatant disregard for conflicts of interest, the president has effectively given a green light to self-interested behavior throughout the government. Such corruption inevitably results in inefficient and unequally provided public services and regulation, with long-term consequences for government effectiveness, and for the public trust essential for democracy to function.

What can be done? Currently, most federal conflicts of interest laws do not apply to the president. There are constitutional issues beyond the scope of this essay as to how far Congress can go but those issues would be worth testing with restrictions targeted on the financial holdings of the president and immediate family members in firms subject to federal oversight or regulation.

An even tougher issue is enforcement. With the DOJ run by Trump loyalists, any enforcement of ethics rules today would be based on the president’s personal interests, not the rules themselves. Some states have adopted independent ethics enforcement institutions, with commissioners appointed by different elected officials and serving for fixed terms, and protected from removal. The Supreme Court’s deepening embrace of the unitary executive theory makes it hard to imagine that a similar federal independent ethics agency could pass constitutional muster. But, as with the substantive restrictions, the constitutional issues are worth testing, and Congress should consider creating an independent, protected ethics watchdog, with enhanced investigative, if not enforcement, authority.

Ultimately, any vindication of the public trust principle will depend on the people. As Madison asked, “Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation.” The last episode of major presidential misconduct – Watergate – led to political and legal reactions that improved the ethical climate, at least for a time. We can hope, and strive for, a similar response this time.

That was quite a week. Over seven days in mid-October,

President Trump hosted a White House dinner for three dozen super-wealthy individuals and representatives of major corporations who pledged funds for his $300 million ballroom.

The president commuted the sentence of former Congressman George Santos, who had served less than three months of an 87-month term for corruption, and canceled Santos’s obligation to pay restitution to his victims.

The president fired, without providing a reason or giving the 30 days’ notice required by law, the Inspector General for the Export-Import Bank.

We learned the president is demanding the Department of Justice pay him $230 million in compensation for federal investigations into his alleged misconduct while a private citizen.

The president pardoned Changpeng Zhao, the billionaire founder of the cryptocurrency exchange Binance, who had previously pleaded guilty to money laundering violations. Binance is a business partner of World Liberty Financial, the crypto venture launched last year by the Trump family.

These developments, each significant in its own right, are but a microcosm of the Trump administration’s broader, two-pronged attack on the ethics foundation of our democracy – the dismantling of the federal ethics structure, coupled with Trump’s unprecedented use of presidential power and influence for private financial gain.

On the structural side, over the last nine months the president fired multiple anti-corruption watchdogs, including the heads of the Office of Government Ethics and the Office of Special Counsel and two dozen Inspectors General. The Department of Justice reduced enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the Foreign Agents Registration Act, gutted its Public Integrity Unit, and dismissed the director of its ethics office; the FBI disbanded its public corruption squad. Trump repeatedly pardoned federal, state, and local officials convicted of public corruption, as well as a host of private fraudsters, thereby undermining the future deterrent effect of federal anti-corruption law.

On the private side, Trump continued his first-term practice of using official meetings and events to promote his private properties. But he has broken new ground in using the power and prestige of the presidency for personal gain by offering White House tours to the individuals who bought the most $TRUMP meme coin; obtaining multimillion-dollar settlements of the libel suits he had brought against media companies that are subject to federal regulation; and securing a $400 million jet from Qatar, which will become property of his foundation when he leaves office. So, too, the Trump family crypto firm has been enriched by transactions with entities, foreign and domestic, that have a stake in U.S. government decisions.

To be sure, President Trump is not the only ethically challenged actor in Washington. Some members of Congress, after an early briefing on the likely impact of COVID on the economy, traded stocks on that information; others continue to trade in stocks of firms influenced by the committees on which they sit. Justices of the Supreme Court have drawn critical scrutiny for accepting, and not disclosing, gifts of luxury travel.

But the president’s destruction of ethics institutions and use of office for private pecuniary benefit are unique in scope and effect.

In our representative democracy, the people we elect to office, and those they appoint, are there to serve the public, not themselves. Henry Clay said it well: “Government is a trust, and the officers of the government are trustees; and both the trust and the trustees are created for the benefit of the people,” not the officeholders. Congress has similarly resolved that any person on government should “never accept, for himself or his family, favors or benefits under circumstances which might be construed by reasonable persons as influencing the performance of his governmental duties.”

This is not just a matter of abstract idealistic theorizing. When public office and private interest are intertwined, it becomes impossible to determine the basis of government decisions. Are crypto-friendly government actions grounded in sound policy judgments or the Trump family’s financial interests? Are the administration’s deals with Persian Gulf potentates based on national security or pecuniary self-interest? Can our leaders even tell public and private reasons apart when public and private interests are so blended?

A fish rots from the head down. By bulldozing the ethics guardrails and demonstrating a blatant disregard for conflicts of interest, the president has effectively given a green light to self-interested behavior throughout the government. Such corruption inevitably results in inefficient and unequally provided public services and regulation, with long-term consequences for government effectiveness, and for the public trust essential for democracy to function.

What can be done? Currently, most federal conflicts of interest laws do not apply to the president. There are constitutional issues beyond the scope of this essay as to how far Congress can go but those issues would be worth testing with restrictions targeted on the financial holdings of the president and immediate family members in firms subject to federal oversight or regulation.

An even tougher issue is enforcement. With the DOJ run by Trump loyalists, any enforcement of ethics rules today would be based on the president’s personal interests, not the rules themselves. Some states have adopted independent ethics enforcement institutions, with commissioners appointed by different elected officials and serving for fixed terms, and protected from removal. The Supreme Court’s deepening embrace of the unitary executive theory makes it hard to imagine that a similar federal independent ethics agency could pass constitutional muster. But, as with the substantive restrictions, the constitutional issues are worth testing, and Congress should consider creating an independent, protected ethics watchdog, with enhanced investigative, if not enforcement, authority.

Ultimately, any vindication of the public trust principle will depend on the people. As Madison asked, “Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation.” The last episode of major presidential misconduct – Watergate – led to political and legal reactions that improved the ethical climate, at least for a time. We can hope, and strive for, a similar response this time.

That was quite a week. Over seven days in mid-October,

President Trump hosted a White House dinner for three dozen super-wealthy individuals and representatives of major corporations who pledged funds for his $300 million ballroom.

The president commuted the sentence of former Congressman George Santos, who had served less than three months of an 87-month term for corruption, and canceled Santos’s obligation to pay restitution to his victims.

The president fired, without providing a reason or giving the 30 days’ notice required by law, the Inspector General for the Export-Import Bank.

We learned the president is demanding the Department of Justice pay him $230 million in compensation for federal investigations into his alleged misconduct while a private citizen.

The president pardoned Changpeng Zhao, the billionaire founder of the cryptocurrency exchange Binance, who had previously pleaded guilty to money laundering violations. Binance is a business partner of World Liberty Financial, the crypto venture launched last year by the Trump family.

These developments, each significant in its own right, are but a microcosm of the Trump administration’s broader, two-pronged attack on the ethics foundation of our democracy – the dismantling of the federal ethics structure, coupled with Trump’s unprecedented use of presidential power and influence for private financial gain.

On the structural side, over the last nine months the president fired multiple anti-corruption watchdogs, including the heads of the Office of Government Ethics and the Office of Special Counsel and two dozen Inspectors General. The Department of Justice reduced enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the Foreign Agents Registration Act, gutted its Public Integrity Unit, and dismissed the director of its ethics office; the FBI disbanded its public corruption squad. Trump repeatedly pardoned federal, state, and local officials convicted of public corruption, as well as a host of private fraudsters, thereby undermining the future deterrent effect of federal anti-corruption law.

On the private side, Trump continued his first-term practice of using official meetings and events to promote his private properties. But he has broken new ground in using the power and prestige of the presidency for personal gain by offering White House tours to the individuals who bought the most $TRUMP meme coin; obtaining multimillion-dollar settlements of the libel suits he had brought against media companies that are subject to federal regulation; and securing a $400 million jet from Qatar, which will become property of his foundation when he leaves office. So, too, the Trump family crypto firm has been enriched by transactions with entities, foreign and domestic, that have a stake in U.S. government decisions.

To be sure, President Trump is not the only ethically challenged actor in Washington. Some members of Congress, after an early briefing on the likely impact of COVID on the economy, traded stocks on that information; others continue to trade in stocks of firms influenced by the committees on which they sit. Justices of the Supreme Court have drawn critical scrutiny for accepting, and not disclosing, gifts of luxury travel.

But the president’s destruction of ethics institutions and use of office for private pecuniary benefit are unique in scope and effect.

In our representative democracy, the people we elect to office, and those they appoint, are there to serve the public, not themselves. Henry Clay said it well: “Government is a trust, and the officers of the government are trustees; and both the trust and the trustees are created for the benefit of the people,” not the officeholders. Congress has similarly resolved that any person on government should “never accept, for himself or his family, favors or benefits under circumstances which might be construed by reasonable persons as influencing the performance of his governmental duties.”

This is not just a matter of abstract idealistic theorizing. When public office and private interest are intertwined, it becomes impossible to determine the basis of government decisions. Are crypto-friendly government actions grounded in sound policy judgments or the Trump family’s financial interests? Are the administration’s deals with Persian Gulf potentates based on national security or pecuniary self-interest? Can our leaders even tell public and private reasons apart when public and private interests are so blended?

A fish rots from the head down. By bulldozing the ethics guardrails and demonstrating a blatant disregard for conflicts of interest, the president has effectively given a green light to self-interested behavior throughout the government. Such corruption inevitably results in inefficient and unequally provided public services and regulation, with long-term consequences for government effectiveness, and for the public trust essential for democracy to function.

What can be done? Currently, most federal conflicts of interest laws do not apply to the president. There are constitutional issues beyond the scope of this essay as to how far Congress can go but those issues would be worth testing with restrictions targeted on the financial holdings of the president and immediate family members in firms subject to federal oversight or regulation.

An even tougher issue is enforcement. With the DOJ run by Trump loyalists, any enforcement of ethics rules today would be based on the president’s personal interests, not the rules themselves. Some states have adopted independent ethics enforcement institutions, with commissioners appointed by different elected officials and serving for fixed terms, and protected from removal. The Supreme Court’s deepening embrace of the unitary executive theory makes it hard to imagine that a similar federal independent ethics agency could pass constitutional muster. But, as with the substantive restrictions, the constitutional issues are worth testing, and Congress should consider creating an independent, protected ethics watchdog, with enhanced investigative, if not enforcement, authority.

Ultimately, any vindication of the public trust principle will depend on the people. As Madison asked, “Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation.” The last episode of major presidential misconduct – Watergate – led to political and legal reactions that improved the ethical climate, at least for a time. We can hope, and strive for, a similar response this time.

About the Author

Richard Briffault

Richard Briffault is the Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation at Columbia Law School. His research, writing, and teaching focus on state and local government law, legislation, the law of the political process, government ethics, and property. In 2014, Briffault was appointed chair of the Conflicts of Interest Board of New York City. He was a member of New York State's Moreland Act Commission to Investigate Public Corruption from 2013 to 2014, and served as a member of, or consultant to, several city and state commissions in New York dealing with state and local governance.

About the Author

Richard Briffault

Richard Briffault is the Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation at Columbia Law School. His research, writing, and teaching focus on state and local government law, legislation, the law of the political process, government ethics, and property. In 2014, Briffault was appointed chair of the Conflicts of Interest Board of New York City. He was a member of New York State's Moreland Act Commission to Investigate Public Corruption from 2013 to 2014, and served as a member of, or consultant to, several city and state commissions in New York dealing with state and local governance.

About the Author

Richard Briffault

Richard Briffault is the Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation at Columbia Law School. His research, writing, and teaching focus on state and local government law, legislation, the law of the political process, government ethics, and property. In 2014, Briffault was appointed chair of the Conflicts of Interest Board of New York City. He was a member of New York State's Moreland Act Commission to Investigate Public Corruption from 2013 to 2014, and served as a member of, or consultant to, several city and state commissions in New York dealing with state and local governance.

About the Author

Richard Briffault

Richard Briffault is the Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation at Columbia Law School. His research, writing, and teaching focus on state and local government law, legislation, the law of the political process, government ethics, and property. In 2014, Briffault was appointed chair of the Conflicts of Interest Board of New York City. He was a member of New York State's Moreland Act Commission to Investigate Public Corruption from 2013 to 2014, and served as a member of, or consultant to, several city and state commissions in New York dealing with state and local governance.

About the Author

Richard Briffault

Richard Briffault is the Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation at Columbia Law School. His research, writing, and teaching focus on state and local government law, legislation, the law of the political process, government ethics, and property. In 2014, Briffault was appointed chair of the Conflicts of Interest Board of New York City. He was a member of New York State's Moreland Act Commission to Investigate Public Corruption from 2013 to 2014, and served as a member of, or consultant to, several city and state commissions in New York dealing with state and local governance.

About the Author

Richard Briffault

Richard Briffault is the Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation at Columbia Law School. His research, writing, and teaching focus on state and local government law, legislation, the law of the political process, government ethics, and property. In 2014, Briffault was appointed chair of the Conflicts of Interest Board of New York City. He was a member of New York State's Moreland Act Commission to Investigate Public Corruption from 2013 to 2014, and served as a member of, or consultant to, several city and state commissions in New York dealing with state and local governance.

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Feb 3, 2026

Cleaner Politics Is as Important as Cleaner Fuels

Bruce E. Cain

Congress, The President & The Courts

Feb 3, 2026

Cleaner Politics Is as Important as Cleaner Fuels

Bruce E. Cain

Congress, The President & The Courts

Feb 3, 2026

Cleaner Politics Is as Important as Cleaner Fuels

Bruce E. Cain

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Feb 3, 2026

Cleaner Politics Is as Important as Cleaner Fuels

Bruce E. Cain

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Feb 3, 2026

Cleaner Politics Is as Important as Cleaner Fuels

Bruce E. Cain

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Feb 3, 2026

Cleaner Politics Is as Important as Cleaner Fuels

Bruce E. Cain

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts