Sep 12, 2025

In the Framers We Trust

Thomas Griffith

Sep 12, 2025

In the Framers We Trust

Thomas Griffith

Sep 12, 2025

In the Framers We Trust

Thomas Griffith

Sep 12, 2025

In the Framers We Trust

Thomas Griffith

Sep 12, 2025

In the Framers We Trust

Thomas Griffith

Sep 12, 2025

In the Framers We Trust

Thomas Griffith

I missed it.

Though it’s been right in front of me for decades, I completely overlooked the most important purpose of the Constitution. I’ve studied the Constitution all my life. I carry a pocket copy everywhere.

I’ve read the best scholarship and built a legal career — as chief counsel to the U.S. Senate, a federal appellate judge, and now a law lecturer — on its foundations. I always believed its purpose was to protect rights and limit government power. And it is. But I now see that the Constitution was also designed to teach us how to live with people we disagree with — a lesson we desperately need today.

I’m one of many who believe we’re in a constitutional crisis, the most serious since the Civil War. But the crisis isn’t about executive overreach or congressional dysfunction. It’s about toxic political polarization — a cancer corroding our civic life. Ironically, many who fuel this polarization claim to be defending the Constitution. Yet, they miss its deeper purpose, just as I once did.

Our public discourse is poisoned by contempt. As Arthur Brooks notes, America is more polarized today than at any time since the Civil War. Surveys show that over 70% of Republicans view Democrats as immoral — and vice versa. Social scientist Jonathan Haidt warns that “(T)here is a very good chance that ... we will have a catastrophic failure of our democracy” because “we just don’t know what a democracy looks like when you drain all trust out of the system.”

Here’s the good news: most Americans are tired of this. And the Constitution itself offers a way out.

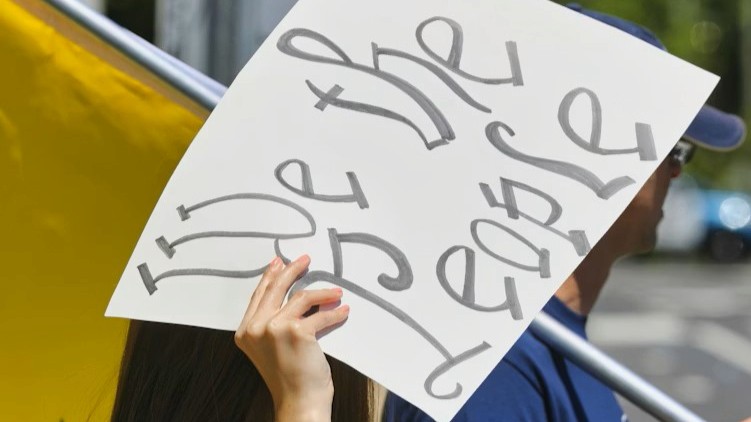

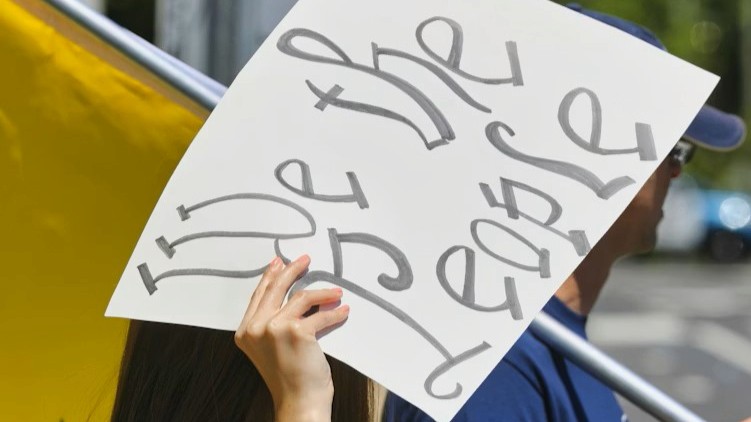

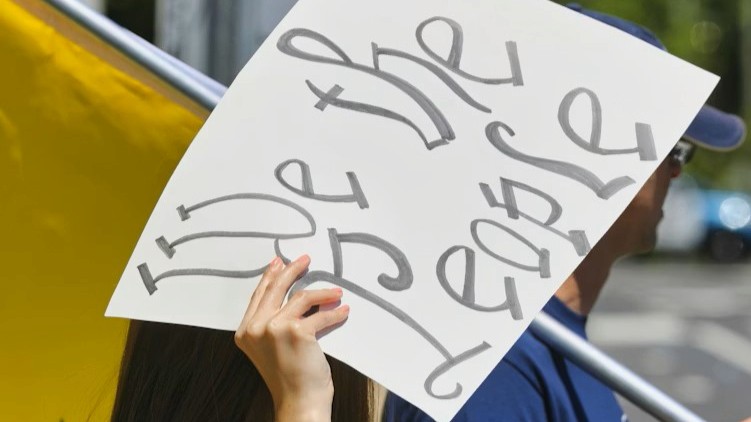

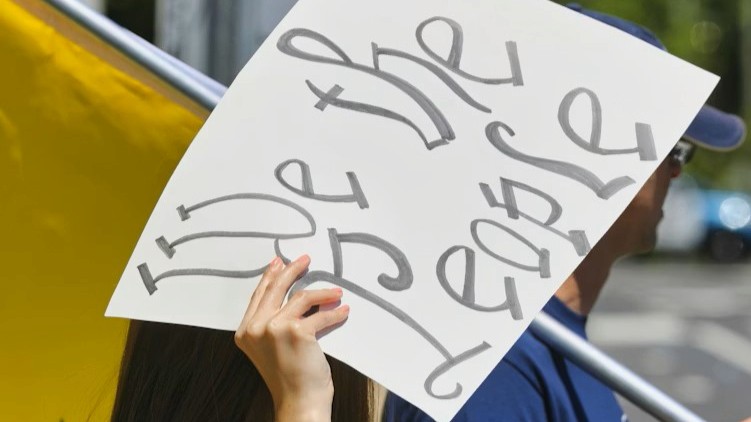

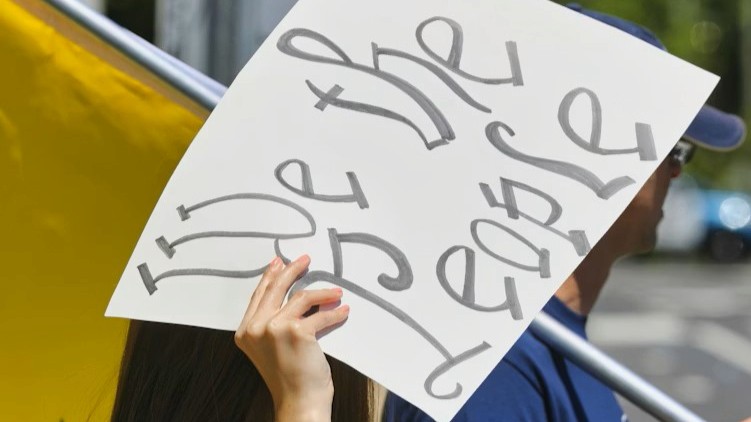

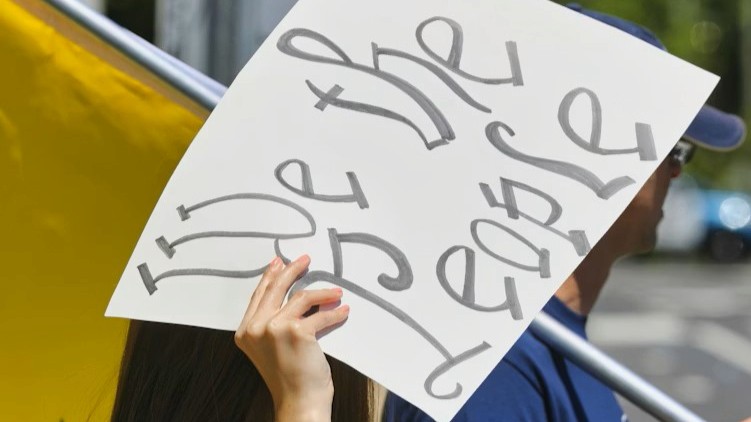

Yuval Levin’s book American Covenant argues that the Constitution isn’t just a charter of rights or a blueprint for government. It’s a framework for national unity amid difference. Think for a moment about the terribly complicated structure of government the Constitution creates. Laws are made by the common action of three different institutions — the House of Representatives, the Senate and the presidency — chosen by different groups of people at different times. This system is not built for efficiency. It is built to slow down proposals in hopes that any law that emerges will be carefully considered and the result of negotiation and compromise among the elected representatives of “We the People.” The structure forces us into relationships of mutual dependence. Levin puts it simply: the Constitution “compels Americans to be a little more accommodating of one another.”

Such a structure demands a new kind of citizen. One who listens to opponents, seeks common ground, and understands that compromise is not betrayal but constitutional duty. As religious leader and legal scholar Dallin Oaks put it, “on contested issues, we should seek to moderate and to unify.” The system works only if citizens of differing views engage in good faith.

Remarkably, this ethos was embedded in the very process that produced the Constitution. By July 1787, the Constitutional Convention was on the brink of collapse. And yet by September, the delegates had struck a deal. George Washington explained how: the Constitution was the result of “a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession, which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable.”

Legal scholar Derek Webb has explored how this spirit was fostered. The Convention’s rules assumed that if you brought people together and had them listen to one another, they’d change their minds. Delegates dined together, socialized, even partied — Benjamin Franklin opened his cellar of port to ease tensions. Over time, men from South Carolina and Massachusetts formed what George Mason called “a proper correspondence of sentiments.” The Framers became friends who were willing to engage in good faith negotiations and seek mutual accommodations for the sake of unity. They did so because their backs were against the wall. Failure to reach compromise would have posed an existential threat to the new nation.

Are we in a similar moment? I fear we are. But the Constitution shows us a path forward. If we’re willing to learn from the Framers — not just what they wrote, but how they wrote it — we can begin to heal. It won’t be easy. It demands humility and generosity. But it also gives us something we’re starving for: hope.

I missed it.

Though it’s been right in front of me for decades, I completely overlooked the most important purpose of the Constitution. I’ve studied the Constitution all my life. I carry a pocket copy everywhere.

I’ve read the best scholarship and built a legal career — as chief counsel to the U.S. Senate, a federal appellate judge, and now a law lecturer — on its foundations. I always believed its purpose was to protect rights and limit government power. And it is. But I now see that the Constitution was also designed to teach us how to live with people we disagree with — a lesson we desperately need today.

I’m one of many who believe we’re in a constitutional crisis, the most serious since the Civil War. But the crisis isn’t about executive overreach or congressional dysfunction. It’s about toxic political polarization — a cancer corroding our civic life. Ironically, many who fuel this polarization claim to be defending the Constitution. Yet, they miss its deeper purpose, just as I once did.

Our public discourse is poisoned by contempt. As Arthur Brooks notes, America is more polarized today than at any time since the Civil War. Surveys show that over 70% of Republicans view Democrats as immoral — and vice versa. Social scientist Jonathan Haidt warns that “(T)here is a very good chance that ... we will have a catastrophic failure of our democracy” because “we just don’t know what a democracy looks like when you drain all trust out of the system.”

Here’s the good news: most Americans are tired of this. And the Constitution itself offers a way out.

Yuval Levin’s book American Covenant argues that the Constitution isn’t just a charter of rights or a blueprint for government. It’s a framework for national unity amid difference. Think for a moment about the terribly complicated structure of government the Constitution creates. Laws are made by the common action of three different institutions — the House of Representatives, the Senate and the presidency — chosen by different groups of people at different times. This system is not built for efficiency. It is built to slow down proposals in hopes that any law that emerges will be carefully considered and the result of negotiation and compromise among the elected representatives of “We the People.” The structure forces us into relationships of mutual dependence. Levin puts it simply: the Constitution “compels Americans to be a little more accommodating of one another.”

Such a structure demands a new kind of citizen. One who listens to opponents, seeks common ground, and understands that compromise is not betrayal but constitutional duty. As religious leader and legal scholar Dallin Oaks put it, “on contested issues, we should seek to moderate and to unify.” The system works only if citizens of differing views engage in good faith.

Remarkably, this ethos was embedded in the very process that produced the Constitution. By July 1787, the Constitutional Convention was on the brink of collapse. And yet by September, the delegates had struck a deal. George Washington explained how: the Constitution was the result of “a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession, which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable.”

Legal scholar Derek Webb has explored how this spirit was fostered. The Convention’s rules assumed that if you brought people together and had them listen to one another, they’d change their minds. Delegates dined together, socialized, even partied — Benjamin Franklin opened his cellar of port to ease tensions. Over time, men from South Carolina and Massachusetts formed what George Mason called “a proper correspondence of sentiments.” The Framers became friends who were willing to engage in good faith negotiations and seek mutual accommodations for the sake of unity. They did so because their backs were against the wall. Failure to reach compromise would have posed an existential threat to the new nation.

Are we in a similar moment? I fear we are. But the Constitution shows us a path forward. If we’re willing to learn from the Framers — not just what they wrote, but how they wrote it — we can begin to heal. It won’t be easy. It demands humility and generosity. But it also gives us something we’re starving for: hope.

I missed it.

Though it’s been right in front of me for decades, I completely overlooked the most important purpose of the Constitution. I’ve studied the Constitution all my life. I carry a pocket copy everywhere.

I’ve read the best scholarship and built a legal career — as chief counsel to the U.S. Senate, a federal appellate judge, and now a law lecturer — on its foundations. I always believed its purpose was to protect rights and limit government power. And it is. But I now see that the Constitution was also designed to teach us how to live with people we disagree with — a lesson we desperately need today.

I’m one of many who believe we’re in a constitutional crisis, the most serious since the Civil War. But the crisis isn’t about executive overreach or congressional dysfunction. It’s about toxic political polarization — a cancer corroding our civic life. Ironically, many who fuel this polarization claim to be defending the Constitution. Yet, they miss its deeper purpose, just as I once did.

Our public discourse is poisoned by contempt. As Arthur Brooks notes, America is more polarized today than at any time since the Civil War. Surveys show that over 70% of Republicans view Democrats as immoral — and vice versa. Social scientist Jonathan Haidt warns that “(T)here is a very good chance that ... we will have a catastrophic failure of our democracy” because “we just don’t know what a democracy looks like when you drain all trust out of the system.”

Here’s the good news: most Americans are tired of this. And the Constitution itself offers a way out.

Yuval Levin’s book American Covenant argues that the Constitution isn’t just a charter of rights or a blueprint for government. It’s a framework for national unity amid difference. Think for a moment about the terribly complicated structure of government the Constitution creates. Laws are made by the common action of three different institutions — the House of Representatives, the Senate and the presidency — chosen by different groups of people at different times. This system is not built for efficiency. It is built to slow down proposals in hopes that any law that emerges will be carefully considered and the result of negotiation and compromise among the elected representatives of “We the People.” The structure forces us into relationships of mutual dependence. Levin puts it simply: the Constitution “compels Americans to be a little more accommodating of one another.”

Such a structure demands a new kind of citizen. One who listens to opponents, seeks common ground, and understands that compromise is not betrayal but constitutional duty. As religious leader and legal scholar Dallin Oaks put it, “on contested issues, we should seek to moderate and to unify.” The system works only if citizens of differing views engage in good faith.

Remarkably, this ethos was embedded in the very process that produced the Constitution. By July 1787, the Constitutional Convention was on the brink of collapse. And yet by September, the delegates had struck a deal. George Washington explained how: the Constitution was the result of “a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession, which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable.”

Legal scholar Derek Webb has explored how this spirit was fostered. The Convention’s rules assumed that if you brought people together and had them listen to one another, they’d change their minds. Delegates dined together, socialized, even partied — Benjamin Franklin opened his cellar of port to ease tensions. Over time, men from South Carolina and Massachusetts formed what George Mason called “a proper correspondence of sentiments.” The Framers became friends who were willing to engage in good faith negotiations and seek mutual accommodations for the sake of unity. They did so because their backs were against the wall. Failure to reach compromise would have posed an existential threat to the new nation.

Are we in a similar moment? I fear we are. But the Constitution shows us a path forward. If we’re willing to learn from the Framers — not just what they wrote, but how they wrote it — we can begin to heal. It won’t be easy. It demands humility and generosity. But it also gives us something we’re starving for: hope.

I missed it.

Though it’s been right in front of me for decades, I completely overlooked the most important purpose of the Constitution. I’ve studied the Constitution all my life. I carry a pocket copy everywhere.

I’ve read the best scholarship and built a legal career — as chief counsel to the U.S. Senate, a federal appellate judge, and now a law lecturer — on its foundations. I always believed its purpose was to protect rights and limit government power. And it is. But I now see that the Constitution was also designed to teach us how to live with people we disagree with — a lesson we desperately need today.

I’m one of many who believe we’re in a constitutional crisis, the most serious since the Civil War. But the crisis isn’t about executive overreach or congressional dysfunction. It’s about toxic political polarization — a cancer corroding our civic life. Ironically, many who fuel this polarization claim to be defending the Constitution. Yet, they miss its deeper purpose, just as I once did.

Our public discourse is poisoned by contempt. As Arthur Brooks notes, America is more polarized today than at any time since the Civil War. Surveys show that over 70% of Republicans view Democrats as immoral — and vice versa. Social scientist Jonathan Haidt warns that “(T)here is a very good chance that ... we will have a catastrophic failure of our democracy” because “we just don’t know what a democracy looks like when you drain all trust out of the system.”

Here’s the good news: most Americans are tired of this. And the Constitution itself offers a way out.

Yuval Levin’s book American Covenant argues that the Constitution isn’t just a charter of rights or a blueprint for government. It’s a framework for national unity amid difference. Think for a moment about the terribly complicated structure of government the Constitution creates. Laws are made by the common action of three different institutions — the House of Representatives, the Senate and the presidency — chosen by different groups of people at different times. This system is not built for efficiency. It is built to slow down proposals in hopes that any law that emerges will be carefully considered and the result of negotiation and compromise among the elected representatives of “We the People.” The structure forces us into relationships of mutual dependence. Levin puts it simply: the Constitution “compels Americans to be a little more accommodating of one another.”

Such a structure demands a new kind of citizen. One who listens to opponents, seeks common ground, and understands that compromise is not betrayal but constitutional duty. As religious leader and legal scholar Dallin Oaks put it, “on contested issues, we should seek to moderate and to unify.” The system works only if citizens of differing views engage in good faith.

Remarkably, this ethos was embedded in the very process that produced the Constitution. By July 1787, the Constitutional Convention was on the brink of collapse. And yet by September, the delegates had struck a deal. George Washington explained how: the Constitution was the result of “a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession, which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable.”

Legal scholar Derek Webb has explored how this spirit was fostered. The Convention’s rules assumed that if you brought people together and had them listen to one another, they’d change their minds. Delegates dined together, socialized, even partied — Benjamin Franklin opened his cellar of port to ease tensions. Over time, men from South Carolina and Massachusetts formed what George Mason called “a proper correspondence of sentiments.” The Framers became friends who were willing to engage in good faith negotiations and seek mutual accommodations for the sake of unity. They did so because their backs were against the wall. Failure to reach compromise would have posed an existential threat to the new nation.

Are we in a similar moment? I fear we are. But the Constitution shows us a path forward. If we’re willing to learn from the Framers — not just what they wrote, but how they wrote it — we can begin to heal. It won’t be easy. It demands humility and generosity. But it also gives us something we’re starving for: hope.

I missed it.

Though it’s been right in front of me for decades, I completely overlooked the most important purpose of the Constitution. I’ve studied the Constitution all my life. I carry a pocket copy everywhere.

I’ve read the best scholarship and built a legal career — as chief counsel to the U.S. Senate, a federal appellate judge, and now a law lecturer — on its foundations. I always believed its purpose was to protect rights and limit government power. And it is. But I now see that the Constitution was also designed to teach us how to live with people we disagree with — a lesson we desperately need today.

I’m one of many who believe we’re in a constitutional crisis, the most serious since the Civil War. But the crisis isn’t about executive overreach or congressional dysfunction. It’s about toxic political polarization — a cancer corroding our civic life. Ironically, many who fuel this polarization claim to be defending the Constitution. Yet, they miss its deeper purpose, just as I once did.

Our public discourse is poisoned by contempt. As Arthur Brooks notes, America is more polarized today than at any time since the Civil War. Surveys show that over 70% of Republicans view Democrats as immoral — and vice versa. Social scientist Jonathan Haidt warns that “(T)here is a very good chance that ... we will have a catastrophic failure of our democracy” because “we just don’t know what a democracy looks like when you drain all trust out of the system.”

Here’s the good news: most Americans are tired of this. And the Constitution itself offers a way out.

Yuval Levin’s book American Covenant argues that the Constitution isn’t just a charter of rights or a blueprint for government. It’s a framework for national unity amid difference. Think for a moment about the terribly complicated structure of government the Constitution creates. Laws are made by the common action of three different institutions — the House of Representatives, the Senate and the presidency — chosen by different groups of people at different times. This system is not built for efficiency. It is built to slow down proposals in hopes that any law that emerges will be carefully considered and the result of negotiation and compromise among the elected representatives of “We the People.” The structure forces us into relationships of mutual dependence. Levin puts it simply: the Constitution “compels Americans to be a little more accommodating of one another.”

Such a structure demands a new kind of citizen. One who listens to opponents, seeks common ground, and understands that compromise is not betrayal but constitutional duty. As religious leader and legal scholar Dallin Oaks put it, “on contested issues, we should seek to moderate and to unify.” The system works only if citizens of differing views engage in good faith.

Remarkably, this ethos was embedded in the very process that produced the Constitution. By July 1787, the Constitutional Convention was on the brink of collapse. And yet by September, the delegates had struck a deal. George Washington explained how: the Constitution was the result of “a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession, which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable.”

Legal scholar Derek Webb has explored how this spirit was fostered. The Convention’s rules assumed that if you brought people together and had them listen to one another, they’d change their minds. Delegates dined together, socialized, even partied — Benjamin Franklin opened his cellar of port to ease tensions. Over time, men from South Carolina and Massachusetts formed what George Mason called “a proper correspondence of sentiments.” The Framers became friends who were willing to engage in good faith negotiations and seek mutual accommodations for the sake of unity. They did so because their backs were against the wall. Failure to reach compromise would have posed an existential threat to the new nation.

Are we in a similar moment? I fear we are. But the Constitution shows us a path forward. If we’re willing to learn from the Framers — not just what they wrote, but how they wrote it — we can begin to heal. It won’t be easy. It demands humility and generosity. But it also gives us something we’re starving for: hope.

I missed it.

Though it’s been right in front of me for decades, I completely overlooked the most important purpose of the Constitution. I’ve studied the Constitution all my life. I carry a pocket copy everywhere.

I’ve read the best scholarship and built a legal career — as chief counsel to the U.S. Senate, a federal appellate judge, and now a law lecturer — on its foundations. I always believed its purpose was to protect rights and limit government power. And it is. But I now see that the Constitution was also designed to teach us how to live with people we disagree with — a lesson we desperately need today.

I’m one of many who believe we’re in a constitutional crisis, the most serious since the Civil War. But the crisis isn’t about executive overreach or congressional dysfunction. It’s about toxic political polarization — a cancer corroding our civic life. Ironically, many who fuel this polarization claim to be defending the Constitution. Yet, they miss its deeper purpose, just as I once did.

Our public discourse is poisoned by contempt. As Arthur Brooks notes, America is more polarized today than at any time since the Civil War. Surveys show that over 70% of Republicans view Democrats as immoral — and vice versa. Social scientist Jonathan Haidt warns that “(T)here is a very good chance that ... we will have a catastrophic failure of our democracy” because “we just don’t know what a democracy looks like when you drain all trust out of the system.”

Here’s the good news: most Americans are tired of this. And the Constitution itself offers a way out.

Yuval Levin’s book American Covenant argues that the Constitution isn’t just a charter of rights or a blueprint for government. It’s a framework for national unity amid difference. Think for a moment about the terribly complicated structure of government the Constitution creates. Laws are made by the common action of three different institutions — the House of Representatives, the Senate and the presidency — chosen by different groups of people at different times. This system is not built for efficiency. It is built to slow down proposals in hopes that any law that emerges will be carefully considered and the result of negotiation and compromise among the elected representatives of “We the People.” The structure forces us into relationships of mutual dependence. Levin puts it simply: the Constitution “compels Americans to be a little more accommodating of one another.”

Such a structure demands a new kind of citizen. One who listens to opponents, seeks common ground, and understands that compromise is not betrayal but constitutional duty. As religious leader and legal scholar Dallin Oaks put it, “on contested issues, we should seek to moderate and to unify.” The system works only if citizens of differing views engage in good faith.

Remarkably, this ethos was embedded in the very process that produced the Constitution. By July 1787, the Constitutional Convention was on the brink of collapse. And yet by September, the delegates had struck a deal. George Washington explained how: the Constitution was the result of “a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession, which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable.”

Legal scholar Derek Webb has explored how this spirit was fostered. The Convention’s rules assumed that if you brought people together and had them listen to one another, they’d change their minds. Delegates dined together, socialized, even partied — Benjamin Franklin opened his cellar of port to ease tensions. Over time, men from South Carolina and Massachusetts formed what George Mason called “a proper correspondence of sentiments.” The Framers became friends who were willing to engage in good faith negotiations and seek mutual accommodations for the sake of unity. They did so because their backs were against the wall. Failure to reach compromise would have posed an existential threat to the new nation.

Are we in a similar moment? I fear we are. But the Constitution shows us a path forward. If we’re willing to learn from the Framers — not just what they wrote, but how they wrote it — we can begin to heal. It won’t be easy. It demands humility and generosity. But it also gives us something we’re starving for: hope.

About the Author

Thomas Griffith

Thomas B. Griffith is a Lecturer on Law at Harvard Law School. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the D. C. Circuit by President George W. Bush in 2005. He retired from the D.C. Circuit in 2020 and is currently Special Counsel at the law firm of Hunton Andrews Kurth, a Fellow at the Wheatley Institute at Brigham Young University, and a member of Utah Valley University's Advisory Board of its Center for Constitutional Studies. In 2021 President Joe Biden appointed him to the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court.

About the Author

Thomas Griffith

Thomas B. Griffith is a Lecturer on Law at Harvard Law School. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the D. C. Circuit by President George W. Bush in 2005. He retired from the D.C. Circuit in 2020 and is currently Special Counsel at the law firm of Hunton Andrews Kurth, a Fellow at the Wheatley Institute at Brigham Young University, and a member of Utah Valley University's Advisory Board of its Center for Constitutional Studies. In 2021 President Joe Biden appointed him to the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court.

About the Author

Thomas Griffith

Thomas B. Griffith is a Lecturer on Law at Harvard Law School. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the D. C. Circuit by President George W. Bush in 2005. He retired from the D.C. Circuit in 2020 and is currently Special Counsel at the law firm of Hunton Andrews Kurth, a Fellow at the Wheatley Institute at Brigham Young University, and a member of Utah Valley University's Advisory Board of its Center for Constitutional Studies. In 2021 President Joe Biden appointed him to the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court.

About the Author

Thomas Griffith

Thomas B. Griffith is a Lecturer on Law at Harvard Law School. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the D. C. Circuit by President George W. Bush in 2005. He retired from the D.C. Circuit in 2020 and is currently Special Counsel at the law firm of Hunton Andrews Kurth, a Fellow at the Wheatley Institute at Brigham Young University, and a member of Utah Valley University's Advisory Board of its Center for Constitutional Studies. In 2021 President Joe Biden appointed him to the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court.

About the Author

Thomas Griffith

Thomas B. Griffith is a Lecturer on Law at Harvard Law School. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the D. C. Circuit by President George W. Bush in 2005. He retired from the D.C. Circuit in 2020 and is currently Special Counsel at the law firm of Hunton Andrews Kurth, a Fellow at the Wheatley Institute at Brigham Young University, and a member of Utah Valley University's Advisory Board of its Center for Constitutional Studies. In 2021 President Joe Biden appointed him to the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court.

About the Author

Thomas Griffith

Thomas B. Griffith is a Lecturer on Law at Harvard Law School. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the D. C. Circuit by President George W. Bush in 2005. He retired from the D.C. Circuit in 2020 and is currently Special Counsel at the law firm of Hunton Andrews Kurth, a Fellow at the Wheatley Institute at Brigham Young University, and a member of Utah Valley University's Advisory Board of its Center for Constitutional Studies. In 2021 President Joe Biden appointed him to the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court.

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts