Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

In this brief note, I will argue for the importance of radically rethinking the core of our constitutional democracies, namely the system of “checks and balances.” The old constitutional scheme appears as a “suit” designed for a “social body” that no longer exists and, therefore, can no longer fulfill the functions for which it was intended. Let me explain.

A plausible version of constitutionalism would say that it was born in pursuit of a “noble dream”: to incorporate all the various sections of society, so as to ensure significant objectives (and here, the “noble dream”): (i) ensuring normative impartiality, since the norms elaborated would be the product of the agreement of all; (ii) guaranteeing political stability, since no group would remain outside the scheme, seeking to destabilize it; and (iii) preventing social oppression, since all incorporated groups could block the enforcement of norms of that type.

In order to make its “noble dream” possible, constitutionalism always insisted on the need to warrant a strong “social correlation” between the institutional framework adopted and the existing social organization. This “correlation” took various forms throughout history. In Greco-Roman antiquity, under the influence of Lycurgus, the idea was to organize a “mixed government” between the King, the aristocracy and the people. In the Middle Ages, power was usually divided among “three estates,” that is, the nobility, the clergy and the peasantry (or, similarly, “those who fight, those who pray and those who work”). By the eighteenth century, power in England was divided between the King, the Lords and the Commons. Consequently, the system of “separation of powers” adopted by the British “balanced constitution” sought to reflect that distribution of power. In the United States, the original notion of the “separation of powers” (reworked by Montesquieu, on the basis of the English Constitution), was slowly transformed into the system of “checks and balances” that we still know today, under a substantially identical logic. As usual, the main assumption was that society was divided into a few, internally homogeneous groups, with stable interests (here, “the few” and “the many”; or “creditors” and “debtors”) which had to be integrated into the system of government, and endowed with equivalent powers. As Alexander Hamilton claimed during the debates in the Federal Convention: "Give all power to the many, they will oppress the few. Give all power to the few, they will oppress the many. Both therefore ought to have power, that each may defend itself against the other." Since the end of the nineteenth century, the “noble dream” was favored by the birth of political parties (i.e., the Labour and Conservative Parties in England; the Communist Party in Italy; the Social-Christian parties in Central Europe; etc.), which allowed the incorporation of broad social sectors in the decision-making process. The “noble dream” was thus preserved: laws continued to be the result of an agreement “among all.”

Unfortunately, after hundreds of years, constitutionalism seems unable to fulfill its “noble dream”: the social and economic conditions that made it conceivable no longer exist. In fact, we live in multicultural societies divided into a multiplicity of internally heterogeneous groups, with diverse and fluctuating interests. Unsurprisingly, our institutions are structurally incapable of accommodating and expressing this radical diversity of interests. Institutions are just unable to do so because the desired “correlation” between institutions and society no longer exists.

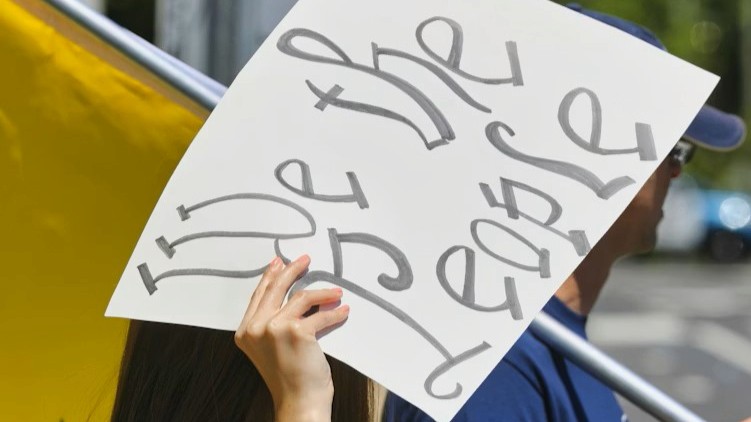

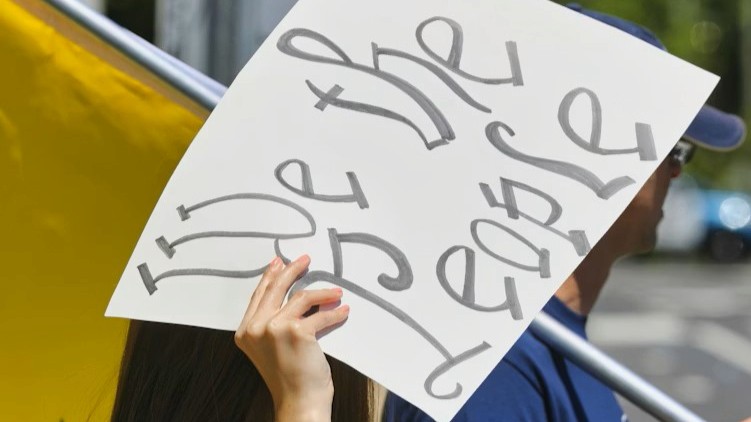

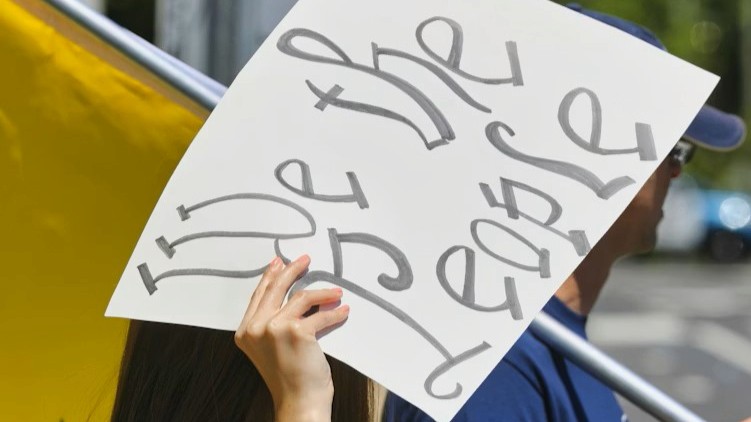

In sum, what we have today is – as announced – an institutional “suit” for a “social body” that no longer exists. In this context, the “noble dream” of constitutionalism cannot be realized. What we then have to expect are situations of normative bias (laws that favor particular groups); political instability (exploited by “populist” leaders); and situations of social oppression (where groups that manage to “colonize” institutional power tend to use that power against their adversaries). Constitutionalism, then, has to get back on its feet, and restore the democratic promises it made when it uttered its first words: “We the People.” Above all, constitutionalism needs to imagine how to enable citizens to regain their voice and controlling powers, acknowledging that the system of “checks and balances” appears exhausted, and structurally incapable of fulfilling its “noble dream.”

In this brief note, I will argue for the importance of radically rethinking the core of our constitutional democracies, namely the system of “checks and balances.” The old constitutional scheme appears as a “suit” designed for a “social body” that no longer exists and, therefore, can no longer fulfill the functions for which it was intended. Let me explain.

A plausible version of constitutionalism would say that it was born in pursuit of a “noble dream”: to incorporate all the various sections of society, so as to ensure significant objectives (and here, the “noble dream”): (i) ensuring normative impartiality, since the norms elaborated would be the product of the agreement of all; (ii) guaranteeing political stability, since no group would remain outside the scheme, seeking to destabilize it; and (iii) preventing social oppression, since all incorporated groups could block the enforcement of norms of that type.

In order to make its “noble dream” possible, constitutionalism always insisted on the need to warrant a strong “social correlation” between the institutional framework adopted and the existing social organization. This “correlation” took various forms throughout history. In Greco-Roman antiquity, under the influence of Lycurgus, the idea was to organize a “mixed government” between the King, the aristocracy and the people. In the Middle Ages, power was usually divided among “three estates,” that is, the nobility, the clergy and the peasantry (or, similarly, “those who fight, those who pray and those who work”). By the eighteenth century, power in England was divided between the King, the Lords and the Commons. Consequently, the system of “separation of powers” adopted by the British “balanced constitution” sought to reflect that distribution of power. In the United States, the original notion of the “separation of powers” (reworked by Montesquieu, on the basis of the English Constitution), was slowly transformed into the system of “checks and balances” that we still know today, under a substantially identical logic. As usual, the main assumption was that society was divided into a few, internally homogeneous groups, with stable interests (here, “the few” and “the many”; or “creditors” and “debtors”) which had to be integrated into the system of government, and endowed with equivalent powers. As Alexander Hamilton claimed during the debates in the Federal Convention: "Give all power to the many, they will oppress the few. Give all power to the few, they will oppress the many. Both therefore ought to have power, that each may defend itself against the other." Since the end of the nineteenth century, the “noble dream” was favored by the birth of political parties (i.e., the Labour and Conservative Parties in England; the Communist Party in Italy; the Social-Christian parties in Central Europe; etc.), which allowed the incorporation of broad social sectors in the decision-making process. The “noble dream” was thus preserved: laws continued to be the result of an agreement “among all.”

Unfortunately, after hundreds of years, constitutionalism seems unable to fulfill its “noble dream”: the social and economic conditions that made it conceivable no longer exist. In fact, we live in multicultural societies divided into a multiplicity of internally heterogeneous groups, with diverse and fluctuating interests. Unsurprisingly, our institutions are structurally incapable of accommodating and expressing this radical diversity of interests. Institutions are just unable to do so because the desired “correlation” between institutions and society no longer exists.

In sum, what we have today is – as announced – an institutional “suit” for a “social body” that no longer exists. In this context, the “noble dream” of constitutionalism cannot be realized. What we then have to expect are situations of normative bias (laws that favor particular groups); political instability (exploited by “populist” leaders); and situations of social oppression (where groups that manage to “colonize” institutional power tend to use that power against their adversaries). Constitutionalism, then, has to get back on its feet, and restore the democratic promises it made when it uttered its first words: “We the People.” Above all, constitutionalism needs to imagine how to enable citizens to regain their voice and controlling powers, acknowledging that the system of “checks and balances” appears exhausted, and structurally incapable of fulfilling its “noble dream.”

In this brief note, I will argue for the importance of radically rethinking the core of our constitutional democracies, namely the system of “checks and balances.” The old constitutional scheme appears as a “suit” designed for a “social body” that no longer exists and, therefore, can no longer fulfill the functions for which it was intended. Let me explain.

A plausible version of constitutionalism would say that it was born in pursuit of a “noble dream”: to incorporate all the various sections of society, so as to ensure significant objectives (and here, the “noble dream”): (i) ensuring normative impartiality, since the norms elaborated would be the product of the agreement of all; (ii) guaranteeing political stability, since no group would remain outside the scheme, seeking to destabilize it; and (iii) preventing social oppression, since all incorporated groups could block the enforcement of norms of that type.

In order to make its “noble dream” possible, constitutionalism always insisted on the need to warrant a strong “social correlation” between the institutional framework adopted and the existing social organization. This “correlation” took various forms throughout history. In Greco-Roman antiquity, under the influence of Lycurgus, the idea was to organize a “mixed government” between the King, the aristocracy and the people. In the Middle Ages, power was usually divided among “three estates,” that is, the nobility, the clergy and the peasantry (or, similarly, “those who fight, those who pray and those who work”). By the eighteenth century, power in England was divided between the King, the Lords and the Commons. Consequently, the system of “separation of powers” adopted by the British “balanced constitution” sought to reflect that distribution of power. In the United States, the original notion of the “separation of powers” (reworked by Montesquieu, on the basis of the English Constitution), was slowly transformed into the system of “checks and balances” that we still know today, under a substantially identical logic. As usual, the main assumption was that society was divided into a few, internally homogeneous groups, with stable interests (here, “the few” and “the many”; or “creditors” and “debtors”) which had to be integrated into the system of government, and endowed with equivalent powers. As Alexander Hamilton claimed during the debates in the Federal Convention: "Give all power to the many, they will oppress the few. Give all power to the few, they will oppress the many. Both therefore ought to have power, that each may defend itself against the other." Since the end of the nineteenth century, the “noble dream” was favored by the birth of political parties (i.e., the Labour and Conservative Parties in England; the Communist Party in Italy; the Social-Christian parties in Central Europe; etc.), which allowed the incorporation of broad social sectors in the decision-making process. The “noble dream” was thus preserved: laws continued to be the result of an agreement “among all.”

Unfortunately, after hundreds of years, constitutionalism seems unable to fulfill its “noble dream”: the social and economic conditions that made it conceivable no longer exist. In fact, we live in multicultural societies divided into a multiplicity of internally heterogeneous groups, with diverse and fluctuating interests. Unsurprisingly, our institutions are structurally incapable of accommodating and expressing this radical diversity of interests. Institutions are just unable to do so because the desired “correlation” between institutions and society no longer exists.

In sum, what we have today is – as announced – an institutional “suit” for a “social body” that no longer exists. In this context, the “noble dream” of constitutionalism cannot be realized. What we then have to expect are situations of normative bias (laws that favor particular groups); political instability (exploited by “populist” leaders); and situations of social oppression (where groups that manage to “colonize” institutional power tend to use that power against their adversaries). Constitutionalism, then, has to get back on its feet, and restore the democratic promises it made when it uttered its first words: “We the People.” Above all, constitutionalism needs to imagine how to enable citizens to regain their voice and controlling powers, acknowledging that the system of “checks and balances” appears exhausted, and structurally incapable of fulfilling its “noble dream.”

In this brief note, I will argue for the importance of radically rethinking the core of our constitutional democracies, namely the system of “checks and balances.” The old constitutional scheme appears as a “suit” designed for a “social body” that no longer exists and, therefore, can no longer fulfill the functions for which it was intended. Let me explain.

A plausible version of constitutionalism would say that it was born in pursuit of a “noble dream”: to incorporate all the various sections of society, so as to ensure significant objectives (and here, the “noble dream”): (i) ensuring normative impartiality, since the norms elaborated would be the product of the agreement of all; (ii) guaranteeing political stability, since no group would remain outside the scheme, seeking to destabilize it; and (iii) preventing social oppression, since all incorporated groups could block the enforcement of norms of that type.

In order to make its “noble dream” possible, constitutionalism always insisted on the need to warrant a strong “social correlation” between the institutional framework adopted and the existing social organization. This “correlation” took various forms throughout history. In Greco-Roman antiquity, under the influence of Lycurgus, the idea was to organize a “mixed government” between the King, the aristocracy and the people. In the Middle Ages, power was usually divided among “three estates,” that is, the nobility, the clergy and the peasantry (or, similarly, “those who fight, those who pray and those who work”). By the eighteenth century, power in England was divided between the King, the Lords and the Commons. Consequently, the system of “separation of powers” adopted by the British “balanced constitution” sought to reflect that distribution of power. In the United States, the original notion of the “separation of powers” (reworked by Montesquieu, on the basis of the English Constitution), was slowly transformed into the system of “checks and balances” that we still know today, under a substantially identical logic. As usual, the main assumption was that society was divided into a few, internally homogeneous groups, with stable interests (here, “the few” and “the many”; or “creditors” and “debtors”) which had to be integrated into the system of government, and endowed with equivalent powers. As Alexander Hamilton claimed during the debates in the Federal Convention: "Give all power to the many, they will oppress the few. Give all power to the few, they will oppress the many. Both therefore ought to have power, that each may defend itself against the other." Since the end of the nineteenth century, the “noble dream” was favored by the birth of political parties (i.e., the Labour and Conservative Parties in England; the Communist Party in Italy; the Social-Christian parties in Central Europe; etc.), which allowed the incorporation of broad social sectors in the decision-making process. The “noble dream” was thus preserved: laws continued to be the result of an agreement “among all.”

Unfortunately, after hundreds of years, constitutionalism seems unable to fulfill its “noble dream”: the social and economic conditions that made it conceivable no longer exist. In fact, we live in multicultural societies divided into a multiplicity of internally heterogeneous groups, with diverse and fluctuating interests. Unsurprisingly, our institutions are structurally incapable of accommodating and expressing this radical diversity of interests. Institutions are just unable to do so because the desired “correlation” between institutions and society no longer exists.

In sum, what we have today is – as announced – an institutional “suit” for a “social body” that no longer exists. In this context, the “noble dream” of constitutionalism cannot be realized. What we then have to expect are situations of normative bias (laws that favor particular groups); political instability (exploited by “populist” leaders); and situations of social oppression (where groups that manage to “colonize” institutional power tend to use that power against their adversaries). Constitutionalism, then, has to get back on its feet, and restore the democratic promises it made when it uttered its first words: “We the People.” Above all, constitutionalism needs to imagine how to enable citizens to regain their voice and controlling powers, acknowledging that the system of “checks and balances” appears exhausted, and structurally incapable of fulfilling its “noble dream.”

In this brief note, I will argue for the importance of radically rethinking the core of our constitutional democracies, namely the system of “checks and balances.” The old constitutional scheme appears as a “suit” designed for a “social body” that no longer exists and, therefore, can no longer fulfill the functions for which it was intended. Let me explain.

A plausible version of constitutionalism would say that it was born in pursuit of a “noble dream”: to incorporate all the various sections of society, so as to ensure significant objectives (and here, the “noble dream”): (i) ensuring normative impartiality, since the norms elaborated would be the product of the agreement of all; (ii) guaranteeing political stability, since no group would remain outside the scheme, seeking to destabilize it; and (iii) preventing social oppression, since all incorporated groups could block the enforcement of norms of that type.

In order to make its “noble dream” possible, constitutionalism always insisted on the need to warrant a strong “social correlation” between the institutional framework adopted and the existing social organization. This “correlation” took various forms throughout history. In Greco-Roman antiquity, under the influence of Lycurgus, the idea was to organize a “mixed government” between the King, the aristocracy and the people. In the Middle Ages, power was usually divided among “three estates,” that is, the nobility, the clergy and the peasantry (or, similarly, “those who fight, those who pray and those who work”). By the eighteenth century, power in England was divided between the King, the Lords and the Commons. Consequently, the system of “separation of powers” adopted by the British “balanced constitution” sought to reflect that distribution of power. In the United States, the original notion of the “separation of powers” (reworked by Montesquieu, on the basis of the English Constitution), was slowly transformed into the system of “checks and balances” that we still know today, under a substantially identical logic. As usual, the main assumption was that society was divided into a few, internally homogeneous groups, with stable interests (here, “the few” and “the many”; or “creditors” and “debtors”) which had to be integrated into the system of government, and endowed with equivalent powers. As Alexander Hamilton claimed during the debates in the Federal Convention: "Give all power to the many, they will oppress the few. Give all power to the few, they will oppress the many. Both therefore ought to have power, that each may defend itself against the other." Since the end of the nineteenth century, the “noble dream” was favored by the birth of political parties (i.e., the Labour and Conservative Parties in England; the Communist Party in Italy; the Social-Christian parties in Central Europe; etc.), which allowed the incorporation of broad social sectors in the decision-making process. The “noble dream” was thus preserved: laws continued to be the result of an agreement “among all.”

Unfortunately, after hundreds of years, constitutionalism seems unable to fulfill its “noble dream”: the social and economic conditions that made it conceivable no longer exist. In fact, we live in multicultural societies divided into a multiplicity of internally heterogeneous groups, with diverse and fluctuating interests. Unsurprisingly, our institutions are structurally incapable of accommodating and expressing this radical diversity of interests. Institutions are just unable to do so because the desired “correlation” between institutions and society no longer exists.

In sum, what we have today is – as announced – an institutional “suit” for a “social body” that no longer exists. In this context, the “noble dream” of constitutionalism cannot be realized. What we then have to expect are situations of normative bias (laws that favor particular groups); political instability (exploited by “populist” leaders); and situations of social oppression (where groups that manage to “colonize” institutional power tend to use that power against their adversaries). Constitutionalism, then, has to get back on its feet, and restore the democratic promises it made when it uttered its first words: “We the People.” Above all, constitutionalism needs to imagine how to enable citizens to regain their voice and controlling powers, acknowledging that the system of “checks and balances” appears exhausted, and structurally incapable of fulfilling its “noble dream.”

In this brief note, I will argue for the importance of radically rethinking the core of our constitutional democracies, namely the system of “checks and balances.” The old constitutional scheme appears as a “suit” designed for a “social body” that no longer exists and, therefore, can no longer fulfill the functions for which it was intended. Let me explain.

A plausible version of constitutionalism would say that it was born in pursuit of a “noble dream”: to incorporate all the various sections of society, so as to ensure significant objectives (and here, the “noble dream”): (i) ensuring normative impartiality, since the norms elaborated would be the product of the agreement of all; (ii) guaranteeing political stability, since no group would remain outside the scheme, seeking to destabilize it; and (iii) preventing social oppression, since all incorporated groups could block the enforcement of norms of that type.

In order to make its “noble dream” possible, constitutionalism always insisted on the need to warrant a strong “social correlation” between the institutional framework adopted and the existing social organization. This “correlation” took various forms throughout history. In Greco-Roman antiquity, under the influence of Lycurgus, the idea was to organize a “mixed government” between the King, the aristocracy and the people. In the Middle Ages, power was usually divided among “three estates,” that is, the nobility, the clergy and the peasantry (or, similarly, “those who fight, those who pray and those who work”). By the eighteenth century, power in England was divided between the King, the Lords and the Commons. Consequently, the system of “separation of powers” adopted by the British “balanced constitution” sought to reflect that distribution of power. In the United States, the original notion of the “separation of powers” (reworked by Montesquieu, on the basis of the English Constitution), was slowly transformed into the system of “checks and balances” that we still know today, under a substantially identical logic. As usual, the main assumption was that society was divided into a few, internally homogeneous groups, with stable interests (here, “the few” and “the many”; or “creditors” and “debtors”) which had to be integrated into the system of government, and endowed with equivalent powers. As Alexander Hamilton claimed during the debates in the Federal Convention: "Give all power to the many, they will oppress the few. Give all power to the few, they will oppress the many. Both therefore ought to have power, that each may defend itself against the other." Since the end of the nineteenth century, the “noble dream” was favored by the birth of political parties (i.e., the Labour and Conservative Parties in England; the Communist Party in Italy; the Social-Christian parties in Central Europe; etc.), which allowed the incorporation of broad social sectors in the decision-making process. The “noble dream” was thus preserved: laws continued to be the result of an agreement “among all.”

Unfortunately, after hundreds of years, constitutionalism seems unable to fulfill its “noble dream”: the social and economic conditions that made it conceivable no longer exist. In fact, we live in multicultural societies divided into a multiplicity of internally heterogeneous groups, with diverse and fluctuating interests. Unsurprisingly, our institutions are structurally incapable of accommodating and expressing this radical diversity of interests. Institutions are just unable to do so because the desired “correlation” between institutions and society no longer exists.

In sum, what we have today is – as announced – an institutional “suit” for a “social body” that no longer exists. In this context, the “noble dream” of constitutionalism cannot be realized. What we then have to expect are situations of normative bias (laws that favor particular groups); political instability (exploited by “populist” leaders); and situations of social oppression (where groups that manage to “colonize” institutional power tend to use that power against their adversaries). Constitutionalism, then, has to get back on its feet, and restore the democratic promises it made when it uttered its first words: “We the People.” Above all, constitutionalism needs to imagine how to enable citizens to regain their voice and controlling powers, acknowledging that the system of “checks and balances” appears exhausted, and structurally incapable of fulfilling its “noble dream.”

About the Author

Roberto Gargarella

Gargarella is Professor of Constitutional Theory and Political Philosophy at the Universidad de Buenos Aires and at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. He has authored and edited more than 25 books in English and Spanish on constitutional theory, political philosophy, and democratic law, with an emphasis on economic and social rights. He has been honored with numerous awards, including a Tinker Scholarship, a Fulbright Scholarship, a Harry Frank Guggenheim Fellowship, and a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.

About the Author

Roberto Gargarella

Gargarella is Professor of Constitutional Theory and Political Philosophy at the Universidad de Buenos Aires and at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. He has authored and edited more than 25 books in English and Spanish on constitutional theory, political philosophy, and democratic law, with an emphasis on economic and social rights. He has been honored with numerous awards, including a Tinker Scholarship, a Fulbright Scholarship, a Harry Frank Guggenheim Fellowship, and a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.

About the Author

Roberto Gargarella

Gargarella is Professor of Constitutional Theory and Political Philosophy at the Universidad de Buenos Aires and at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. He has authored and edited more than 25 books in English and Spanish on constitutional theory, political philosophy, and democratic law, with an emphasis on economic and social rights. He has been honored with numerous awards, including a Tinker Scholarship, a Fulbright Scholarship, a Harry Frank Guggenheim Fellowship, and a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.

About the Author

Roberto Gargarella

Gargarella is Professor of Constitutional Theory and Political Philosophy at the Universidad de Buenos Aires and at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. He has authored and edited more than 25 books in English and Spanish on constitutional theory, political philosophy, and democratic law, with an emphasis on economic and social rights. He has been honored with numerous awards, including a Tinker Scholarship, a Fulbright Scholarship, a Harry Frank Guggenheim Fellowship, and a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.

About the Author

Roberto Gargarella

Gargarella is Professor of Constitutional Theory and Political Philosophy at the Universidad de Buenos Aires and at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. He has authored and edited more than 25 books in English and Spanish on constitutional theory, political philosophy, and democratic law, with an emphasis on economic and social rights. He has been honored with numerous awards, including a Tinker Scholarship, a Fulbright Scholarship, a Harry Frank Guggenheim Fellowship, and a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.

About the Author

Roberto Gargarella

Gargarella is Professor of Constitutional Theory and Political Philosophy at the Universidad de Buenos Aires and at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. He has authored and edited more than 25 books in English and Spanish on constitutional theory, political philosophy, and democratic law, with an emphasis on economic and social rights. He has been honored with numerous awards, including a Tinker Scholarship, a Fulbright Scholarship, a Harry Frank Guggenheim Fellowship, and a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts

More viewpoints in

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 29, 2026

Checks and Balances, Democracy, and the "Noble Dream" of Constitutionalism

Roberto Gargarella

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

"What's Next?" at the NYU Law Democracy Project

Faculty Directors

Congress, The President & The Courts

Jan 27, 2026

The Power of the Purse: A Symptom of a Larger Institutional Decline

Shalanda Young

Congress, The President & The Courts